The debate over natural wine has raged on for years now. To some wine aficionados, it is the only wine that matters, to others it is all but undrinkable. This debate—whether to love, hate, or disregard “natural” wine—will surely continue for generations.

However, it seems that the industry is inching closer to the goal of codifying a definition of “natural wine.” A few regions have even agreed to disagree on a definition, including—according to multiple recent news sources—the mother ship of wine producers, France.

This information was first brought to our attention via the publication of the headline La Dénomination “Vin Méthode nature” Officiellement Reconnue (“The name wine–nature method is officially recognized”)—published on March 6, 2020 via food-and-wine journal Atabula.

Before we bang the gong too loudly, there are a few things to note about this latest development. For starters, it does appear to be quite relevant in that France has agreed upon the parameters of natural wine. However, it should be noted that due to previous laws prohibiting the use of the term “natural” on wine labels, the approved term is Vin Méthode Nature (“nature method wines”)—NOT naturel nor naturelle.

In addition, approval of the label term has not yet been announced by the INAO, nor published on the website of the Ministère de l’agriculture et de l’alimentation (French Ministry of Agriculture and Food). Nevertheless, it has been approved by the Directorate General for Competition, Consumption and the Suppression of Fraud (la Direction générale de la Concurrence, de la Consommation et de la Répression des frauds/DGCCRF) that previously opposed the use of the term “natural.” As such, the term “Vin Méthode Nature” has been approved as a validated private label and may soon appear on bottles of French wine. Compliance wit the charter will enforced by the DGCCRF.

The effort to have the new label approved has been spearheaded by Le Syndicat Vins Nature’l (the Union of Natural Wines), presided over by Jacques Carroget (proprietor of Domaine la Paonnerie in France’s Loire Valley). It is estimated that up to sixty wines may apply to be granted use of the term (and logo) for the release of the 2019 vintage.

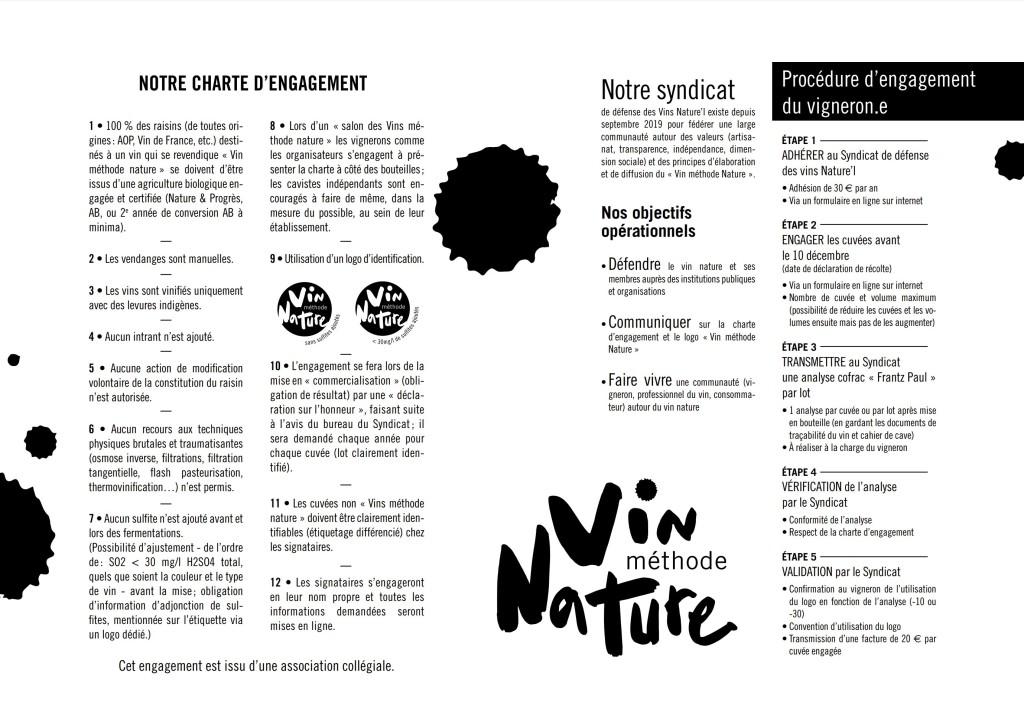

According to the new regulations, the following is required in order to use the label term Vin Méthode Nature and the logo:

- Vineyards must be organically farmed, as represented by organic certification, second-year organic conversion, or private Nature and Progress charter

- Grapes must be hand-harvested

- Use of indigenous yeasts

- No sulfur added before or during fermentation. Note that there are two versions of the logo available, one that declares “without added sulfites” (for wines containing less than 10 mg/L); and one that declares “less than 30 mg sulfites.”

- No must adjustments (acidification, chaptalization, etc.)

- No “recourse to brutal and traumatic physical techniques,” which specifically excludes reverse osmosis, filtration, flash pasteurization, and thermovinification.

- Click here to see the entire list via the Charter of Syndicat de défense des Vins Nature’l

We’ll be watching for updates and will post more information on these developments as they are released.

References/for more information:

- https://www.bio-centre.org/index.php/a-la-une/329-naissance-du-syndicat-de-defense-des-vins-nature-l

- https://www.bfmtv.com/economie/la-denomination-vin-methode-nature-officiellement-reconnue-1870570.html?fbclid=IwAR1Do3sMnI_3MMeHFDUYhP-LzfWi0j2eSK67gAUPX99VafZpl46M1CpiX8w

- https://www.vitisphere.com/actualite-91380-Vin-methode-nature-en-phase-de-reconnaissance-administrative.htm

- https://www.lapaonnerie.com/

- https://www.winebusiness.com/news/?go=getArticle&dataId=228237