.

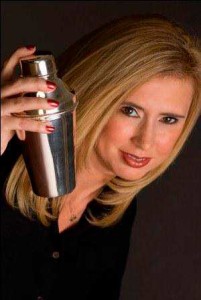

Master Distiller Lincoln Henderson once dubbed her “The Queen of Bourbon,” and in her stellar career Trudy Thomas has truly lived into that title, having recently become one of the few to achieve the Certified Spirits Educator designation from the SWE.

Trudy has a fascinating history. She grew up in rural Kentucky, where she was introduced into the rich tradition of moonshine by her grandfather, who distilled his own spirits, flavored with fresh fruit and peppermint. He even made copper coils for other distillers, one of which remains on display at the county courthouse. She would watch him as he worked, sneaking tastes, learning from him—and become inspired by the passion and fire he had for what he did.

Despite this beginning, Trudy never intended to enter into the spirits industry. She was a percussionist while at the University of Kentucky and dreamed of being a musician. Later, she graduated with a degree in speech therapy after an injury prompted a change in direction.

However, the past has a way of circling back around, though, and the fire and passion instilled by her grandfather found an outlet for Trudy first in bartending, then in the food and beverage industry as a whole. Following this passion, she joined Spago Beverly Hills, where she was under the tutelage of Chef Wolfgang Puck for a period of four years.

.

In 2008 she joined the JW Marriott Camelback Inn in Scottsdale, Arizona, to raise the bar on their beverage program. In 2014 she joined the Gaylord Opryland property (managed by Marriott), where she is currently Director of Beverage, overseeing beverage for more than 20 outlets and banquets.

Trudy had been a judge of spirits and wine at BTI in Chicago, and also at the San Francisco Spirits Competition, and honed her skills in the evaluation of spirits. While in Arizona, she decided to study for the CSW and the CSS, and was the first person to take and pass both examinations on the same day. When the Society of Wine Educators introduced the CSE designation, she knew it was something that she wanted for herself both personally and professionally. Preparing for the exam while working at Gaylord Opryland proved a challenge, with stops and starts along the way, requiring discipline to set aside the time to study. With preparation help from fellow bartenders on evaluations and blind tastings, she passed the tasting portions of the exam; and returned later to take the multiple choice and essays. Her presentation was on bourbon heritage in the America.

.

To listen to Trudy reflect on her career, though, is to hear a story about the value of mentors and teachers, and of her appreciation for the many people along the way who mentored her in her own work, the likes of Lincoln Henderson, Parker Beam, Dave Pickerel, Bill Samuels, and Jimmy Russell, and other giants in the spirits industry. She writes of the gentlemen who were so influential in her life: “These legends are/were like fathers, kicking me in the behind when I needed it, most of the time they tried to restrain my fire and encourage my passion but they always believed in me and pushed me to the next level for success; they helped me to test my limits while remembering to never sacrifice loyalty; they gave me wings to fly while keeping my roots always planted in Kentucky soil. These mentors were both my heritage and my future.”

What’s next for Trudy? First, she wants to continue to grow and improve the beverage programs for Marriott, and specifically at the Gaylord Opryland. But most inspiring is her desire to instill in others the passion she feels for her craft, as those who came before had done for her. “My biggest goal is to mentor others as I have been mentored, I truly want to give back to an industry which believed in me, a bartender with roots in rural Kentucky, and which has given me so many amazing opportunities and experiences, an industry with lifelong friends. I had great mentors, I hope to be the same and pay it forward while making my mentors proud.”

Guest post written by Reverend Paul Bailey