Spending New Year’s Eve in Rome, I was able to observe and enjoy Italy’s dual personality in sparkling wine. Prosecco was sold by street vendors and enjoyed alfresco; sitting on the Spanish Steps, watching fireworks in Piazza del Popolo or enjoying the concert at Circus Maximus. Franciacorta was pouring inside Rome’s many Enotecas and Ristorantes.

Spending New Year’s Eve in Rome, I was able to observe and enjoy Italy’s dual personality in sparkling wine. Prosecco was sold by street vendors and enjoyed alfresco; sitting on the Spanish Steps, watching fireworks in Piazza del Popolo or enjoying the concert at Circus Maximus. Franciacorta was pouring inside Rome’s many Enotecas and Ristorantes.

While both Prosecco and Franciacorta are sparkling wines, there are more differences than just where they are enjoyed.

In the Piazza – Prosecco!

Prosecco is often considered fun, easy to drink, perfect during happy hour and inexpensive – generally a wine for every occasion. Prosecco has been produced in northeastern Italy going back as far as Roman times using the Glera grape variety, which grew near the village of Prosecco. Cultivation spread to the hills of Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia in the 18th century and there is early documentation that due to Prosecco’s aromatic quality it is suitable for producing wine with a fine sensory profile.

Production continued to spread to the lower lying areas of Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia and this is where the Prosecco we know today was first produced in the beginning of the 20th century, thanks to the introduction of a new secondary fermentation technique. Scientific knowledge has come leaps and bounds later in the 20th century, which perfected the Prosecco production method.

Prosecco first received Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC) status in 1969 for sparkling wines produced in the hills near the towns of Conegliano and Valdobbiadene. In 2009 major changes to the Prosecco disciplinare were implemented:

- Prosecco is now strictly defined as a wine-producing region. Therefore, the grape used should no longer be referred to as “Prosecco” and is now correctly identified as Glera.

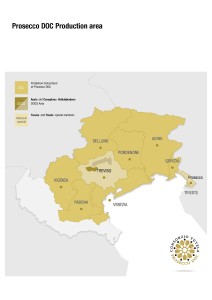

- The Prosecco DOC was expanded to replace the previous Indicazione Geografica Tipica (IGT) region in northeastern Italy. The Prosecco DOC now encompasses nine provinces in the regions of Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia. This introduced stricter controls and greater guarantees for the consumer.

- Prosecco Superiore was elevated to Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) status. DOCG wines include Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco DOCG and Colli Asolani (Asolo) Prosecco DOCG.

- The “crus” Rive and Cartizze are new introductions. Il Rive is reserved for sparkling wines which highlight individual communes or hamlets in the Conegliano-Valdobbiadene area enabling individual expression. “Rive” in local dialect translates as “vineyards planted on steep land.” Superiore di Cartizze is the peak of DOCG quality and is considered the “grand cru” of Prosecco. Cartizze is comprised of 107 hectares of remarkably steep vineyards of San Petro di Barbozza, Santo Stefano, and Saccol in the commune of Valdobbiadene. This micro area is a perfect combination of mild climate, aspect and soils. The vineyards here produce a sparkling wine of particular elegance which represents the maximum expression of the Conegliano-Valdobbiadene area.

Prosecco must be made with a minimum of 85% Glera while the remaining 15% can be of any combination of Verdiso, Perera, Bianchetta, Glera Lugna, Pinot Bianco, Pinot Grigio, Chardonnay, or Pinot Nero (only if produced as a white wine).

Prosecco is generally made in the Charmat or “Italian Method,” defined as the second fermentation taking place in large pressurized stainless steel tanks with the addition of sugar and yeast. This second fermentation lasts a minimum of 30 days. Once finished, the sparkling wine is bottled and ready to be released into the market. This method allows the preservation of the grapes’ varietal aromas, giving a fruity and floral wine.

Prosecco can either be produced as full sparkling (Spumante) or lightly sparkling (Frizzante or gentile). Then the specific style is designated by the residual sugar content.

- Brut – maximum of 12 grams per liter of residual sugar

- Extra Dry – between 12-17 grams per liter

- Dry – between 17-32 grams per liter

Prosecco is low in alcohol with only 11 to 12% alcohol by volume and low in pressure with 3 atmospheres of pressure for the Spumante and 1 to 2 ½ atmospheres of pressure for the Frizzante.

Prosecco is usually enjoyed “straight,” but also appears in some popular cocktails, such as the Bellini (Peach and Prosecco), the Spritz (Aperol, Compari, Cynar), or the Sgroppino (Lemon sorbet, Prosecco and vodka).

In the Enoteca – Franciacorta!

If the French will forgive me for saying this, Franciacorta is the Italians’ response to Champagne. The wines of Franciacorta have been around a long time – mention of the area’s wines appeared in one of the first published works about the technique of production of natural fermentation wines in the bottle and their beneficial and therapeutic action on the human body – printed in 1570.

The Franciacorta DOCG is located in Lombardy’s province of Bescia, within the territory of Franciacorta. Lake Iseo moderates the climate while the hills to the east and west protect the region from winds. Soils are mostly morainic, laid down by the glaciers that formed the lakes and valleys.

Franciacorta was the first Italian sparkling wine produced by the Classic Method (second fermentation in the bottle) awarded Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) in 1995. Today, the wine reads simply “Franciacorta”: this defines the growing area, the production method, and the wine. There are only ten such wines in all of Europe and only three of them are sparkling: Champagne, Cava and Franciacorta.

Franciacorta today is still a relatively small region with 2,700 hectares under vine and around 100 producers. The Franciacorta DOCG limits the varieties to Chardonnay, Pinot Nero and Pinot Blanco. It also regulates yields, harvesting times, conditions and many other aspects of winemaking. Fanciacorta enjoys a long secondary fermentation in the bottle and is aged for many years before release. While universally known as sparkling wine made in the traditional method, locally this process is referred to as the “Franciacorta method”.

The categories of Franciacorta are:

- Non-vintage – Aged on its lees for 18 months and not released until at least 25 months after harvest. Chardonnay and/or Pinot Noir, with up to 50% Pinot Bianco. Produced in a range of styles: Pas dosé, Extra Brut, Brut, Extra Dry, Sec, or Demi-Sec.

- Satèn – Aged on its lees for 24 months. Satèn is always blanc de blancs made predominantly of Chardonnay with up to 50% Pinot Bianco allowed. Satèn is bottled at a slightly lower pressure (less than 5 atmospheres of pressure instead of the standard 6 atmospheres) giving it a softer mouthfeel. Produced in only the Brut style.

-

Rosé – Aged on its lees for 24 months. Rosé is often made from just Pinot Noir grapes, but may also be made by blending a minimum of 25% Pinot Noir with base wines of Chardonnay and/or Pinot Bianco. Produced in a range of styles: Pas dosé, Extra Brut, Brut, Extra-Dry, Sec, or Demi-Sec.

- Millesimato (Vintage) – Aged on its lees for 30 months and not released until at least 37 months after harvest. At least 85% of the base wine must come from one single growing year. Both Satèn and Rose can include Millesimato. Produced in a range of styles: Pas dosé, Extra Brut, Brut, Extra Dry (Satèn only Brut)

- Riserva – Is a Millesimato (can include Satèn and Rose) which is aged on its lees at least 60 months and not released until at least 67 months (5 ½ years) after harvest. Since many Franciacorta Millesimatos rest sur lie far longer than the required minimum of 30 months, this designation was created to highlight this unique type of wine. Produced in a range of styles: Pas dosé, Extra Brut, Brut (Satèn only Brut)

The dosato of Franciacorta are defined in the same way as Champagne’s dosage levels.

- Pas dosé (No dosage, dosage zero, pas opéré or nature) – maximum 3 grams per liter residual sugar

- Extra Brut – maximum 6 grams per liter

- Brut – maximum 12 grams per liter

- Extra Dry – between 12-17 grams per liter

- Sec (Dry) – between 17-32 grams per liter

- Demi Sec – between 32-50 grams per liter

So…now that you know the details – how would you rather spend New Year’s Eve in Roma? Would you like to welcome the stroke of midnight with Prosecco on the piazza, or Franciacorta in the enoteca?

Post authored by Brenda Audino, CWE. After a long career as a wine buyer with Twin Liquors in Austin, Texas, Brenda has recently moved to Napa, California (lucky!)where she runs the Spirited Grape wine consultancy business. Brenda is a long-time member of SWE and has attended many conferences – be sure to say “hi” at this year’s conference in NOLA!