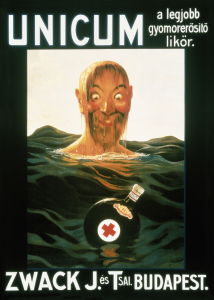

Produced in Budapest, Hungary; Unicum is a bold, bitter liqueur created using over 40 different botanicals. Unicum was invented in 1790 by Dr. József Zwack, Royal Physician to the Hungarian Court, in order to settle the stomach of Emperor Joseph II, then the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Hungary.

Produced in Budapest, Hungary; Unicum is a bold, bitter liqueur created using over 40 different botanicals. Unicum was invented in 1790 by Dr. József Zwack, Royal Physician to the Hungarian Court, in order to settle the stomach of Emperor Joseph II, then the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Hungary.

The beverage is said to have received its name when Emperor Joseph proclaimed, “Dr. Zwack, das ist ein Unicum!” meaning the drink was “rather unique!”

In 1840, the Doctor’s son, József Junior, founded J. Zwack & Partners, the first Hungarian liqueur manufacturer. Soon, J. Zwack & Partners was one of the leading distilleries in Eastern Europe, producing over 200 varieties of spirits and liqueurs and exporting them all over the world. The distillery was handed down through the generations of the family and successfully operated until the facility was completely destroyed during World War II.

After the war, in 1948, the distillery was seized from the Zwack family and nationalized by the Communist regime. János and Péter Zwack, the grandson and great-grandson of the founder, escaped the country with the original Zwack recipe. Another grandson, Béla, remained behind to give the regime a “fake” Zwack recipe and became a regular factory worker.

Meanwhile, János and Péter migrated to the United States and settled in the Bronx. Péter worked diligently in the liquor trade and entered into an agreement with the Jim Beam Company to produce and distribute products under the Zwack name.

Meanwhile, János and Péter migrated to the United States and settled in the Bronx. Péter worked diligently in the liquor trade and entered into an agreement with the Jim Beam Company to produce and distribute products under the Zwack name.

In 1988, one year before the fall of the communist regime, Péter returned to Hungary in 1988 and repurchased the Zwack production facility from the state. By 1990, the production of the original Zwack formula and many other products resumed in Budapest.

The Zwack Company has since recovered its position as the leading distillery of Eastern Europe and is now run by the sixth generation of the Zwack family.

Click here to visit the Zwack Website

Click here to return to the SWE Website.