Today we have a guest post from Brenda Audino, CWE. Brenda tells us about her brush with Flash Détente – very interesting!

Today we have a guest post from Brenda Audino, CWE. Brenda tells us about her brush with Flash Détente – very interesting!

I recently tasted a modest (read inexpensive) wine that had a bright purple hue and Jolly Rancher fruit aromas. I enquired whether the wine had undergone Carbonic Maceration as it seemed to fit that profile. It was explained to me that although the results are similar, this particular wine was produced using Flash Détente technology. Being ever curious, I wondered what is Flash Détente; when, why and how is it used in the wine production.

To explain Flash Détente, we need to understand that one of the principal goals in producing red wine is the extraction of color and flavor from the skins. This extraction is usually achieved by a combination of maceration and fermentation. Here is a review of three popular means for extraction including the new (to me) Flash Détente.

Classic maceration is achieved at low temperatures of 24-32°C (75-90°F) requiring extended contact between the juice and grape skins. The fermentation process, while producing alcohol, also extracts the polyphenols from the skins. One of the byproducts of fermentation is the release of CO2 which raises the skins to the surface forming a floating cap. This floating cap is subject to acetic bacteria as well as other contaminates and, if left exposed to the air, can turn the entire batch into vinegar. A floating cap also does nothing to extract further color and flavors into the juice. It is therefore necessary to mix the skins back into the juice by one of many processes (punch down, pump over, rack and return, etc.)

Thermo-vinification uses heat to extract color and flavors from the skins. The crushed grapes are heated to 60-75°C (140-167°F) for 20 to 30 minutes. The must is then cooled down to fermentation temperature. This process gives intensely colored must because the heat weakens the cell walls of the grape skins enabling the anthocyanins to be easily extracted. This process can result in the wine having a rather “cooked” flavor.

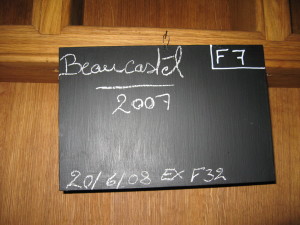

While I was researching these technologies, I recalled a previous visit to Château de Beaucastel where I learned that make their iconic wine using a modified process of Thermo-vinification. At Château de Beaucastel, the grapes are de-stemmed and the uncrushed grapes are passed rapidly through a heat exchanger at 90°C (194°F) which only heats the surface of the grapes, not the juice. The heat is sufficient to weaken the cell wall of the grape skins enabling for easier extraction of anthocyanins, since the juice is kept cool the wine is less likely to have any cooked flavors due to this modified process.

While I was researching these technologies, I recalled a previous visit to Château de Beaucastel where I learned that make their iconic wine using a modified process of Thermo-vinification. At Château de Beaucastel, the grapes are de-stemmed and the uncrushed grapes are passed rapidly through a heat exchanger at 90°C (194°F) which only heats the surface of the grapes, not the juice. The heat is sufficient to weaken the cell wall of the grape skins enabling for easier extraction of anthocyanins, since the juice is kept cool the wine is less likely to have any cooked flavors due to this modified process.

Flash Détente is essentially an evolution of the traditional thermo-vinification method. The process involves a combination of heating the grapes to about 82°C (180°F) and then sending them into a huge vacuum chamber where they are cooled. During this cooling process the cells of the grape skins burst from the inside making a distinct popping noise. Similar to traditional thermo-vinification, this process enables better extraction of anthocyanins and flavor compounds.

The Flash Détente process creates a steam that is diverted to a condenser. This steam is loaded with aromatic compounds including pyrazines (vegetal, green pepper and asparagus). Because vapor is removed, the sugar level increases in the remaining must. The winemaker can choose to work with the higher sugar levels or dilute back down by adding water. Most winemakers discard the condensation or “Flash Water” as the aromatics are usually highly disagreeable. The winemaker now has multiple choices. The flashed grapes can be pressed and fermented similar to white wine, the must can be fermented with the skins in the more traditional red wine production manner, or the flashed grapes can be added to non-flashed must that underwent classic maceration and then co-fermented.

Flash technology differs from traditional thermo-vinification because the traditional method does not involve a vacuum and there is no flash water waste produced. Winemakers who are familiar with both methods have noted that the tannin extraction with thermo-vinification is less than Flash Détente. Winemakers also note that Flash technology is better for removing pyrazine aromas.

In Europe during the early years of flash technology, it was mainly used for lower quality grapes or difficult vintages that had problems needing fixed. Now the use of this technology is expanding its application to all quality levels of the wine industry.

In Europe during the early years of flash technology, it was mainly used for lower quality grapes or difficult vintages that had problems needing fixed. Now the use of this technology is expanding its application to all quality levels of the wine industry.

According to Linda Bisson, a professor of viticulture and enology at UC Davis and one of the researchers working on the project, enologists are looking at what characteristics are lost or retained per grape variety. They are also looking at the character and structure of tannins in flashed wines. Bisson states that turning flashed grapes into a standalone wine is possible, but most winemakers see it as a tool for creating blends. “It’s something on your spice rack to blend back in.”

The use of Flash Détente can be surmised as “It’s an addition to traditional winemaking, not a replacement.”

What are your thoughts on technology in the wine industry? Does technology improve the wine or make it more homogenous?

Photos and post by Brenda Audino, CWE. After a long career as a wine buyer with win Liquors in Austin, Texas, Brenda has recently moved to Napa, California (lucky!) where she runs the Spirited Grape wine consultancy business. Brenda is a long-time member of SWE and has attended many conferences – be sure to say “hi” at this year’s conference in NOLA!

Are you interested in being a guest blogger or a guest SWEbinar presenter for SWE? Click here for more information!