Today we have a guest post from Evan Davis, CS, WSET 3, CSW. Evan tells us a bit about what he learned during a recent trip through the winelands of Georgia.

While many countries and emerging regions of the world have made their bones attempting to grow familiar French grape varieties, in the country of Georgia, winery owners have taken a different approach. All chips are in on traditional Georgian grape varieties.

While many countries and emerging regions of the world have made their bones attempting to grow familiar French grape varieties, in the country of Georgia, winery owners have taken a different approach. All chips are in on traditional Georgian grape varieties.

Travel to Georgia, and you’ll enter a world apart and distinctly different from the rest of the wine world. Not leastways because of the long and oppressive Soviet regime, which—beginning in the 1920s—effectively ended winemaking as a free and commercial enterprise until the dissolving of the Soviet Union in 1991. In fact, of the nearly 125 million 750ml bottles exported in 2022, over 87 million of those bottles were exported to Russia. This is around 70%—and, with the US export share being a mere 1.1 million bottles, this is something the Georgians are hoping to change.

Just how are they going to accomplish this? With an intense focus on their strengths. Ask any Georgian winery owner what the most important strength of their winemaking heritage is, and you’ll get several answers. The nearly 8000-year history of making wine, the practice of making wine in Qvevri, and the veritable kaleidoscope of their indigenous grape varieties to name a few.

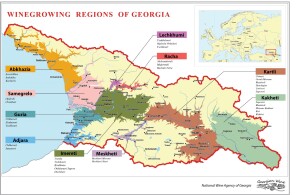

Georgia currently boasts as many as 525 endemic grape varieties. Of these, approximately 30 are used in commercial agriculture today. As a matter of fact, the country’s main wine region—Khaketi in eastern Georgia—is planted almost entirely with just a few leading grape varieties. However, even with these (5 or 6) most commonly planted grapes, a wealth of tasting experiences awaits the wine lover.

Georgia currently boasts as many as 525 endemic grape varieties. Of these, approximately 30 are used in commercial agriculture today. As a matter of fact, the country’s main wine region—Khaketi in eastern Georgia—is planted almost entirely with just a few leading grape varieties. However, even with these (5 or 6) most commonly planted grapes, a wealth of tasting experiences awaits the wine lover.

All the main grape varieties are made in both Qvevri and the “western” or modern style. The use of Qvevri—large handmade clay fermentation vessels buried in the ground—represents the ancient and unique practice of winemaking in Georgia. Alternatively, the western (modern) style of winemaking is focused on taking advantage of technological advances to produce clean, varietally correct wines using less labor-intensive production methods.

Rkatsitelli for example, is one of the most planted grape varieties in Georgia. At 63% of the total harvest in 2022, this thick-skinned white grape variety is the darling of Georgian winemakers. Rkatsitelli translates to “red horn” referring to the reddish hue the stems of this variety develop when lignified. When produced in the western style, it produces bright, tangy wines with crisp acidity and notes of lime zest, green apple, fennel and tarragon. If made in Qvevri, the wines take on a whole new character and complexity of texture, displaying aromas and flavors of dried orange peel, marmalade, dried flowers and curry spices. Fenugreek and coriander come to mind.

Mtsvane on the other hand, is a thinner-skinned white grape variety that has much more pronounced floral tones. It is a very successful blending partner to Rkatsitelli. This is particularly true in the wines from the region of Tsinandali, considered to be Georgia’s flagship white wine. While still bright and crisp, Tsinandali wines have an extra dimension of texture, intensity and floral lift not present in 100% Rkatsitelli wines. Tsinandali wines are not made in Qvevri, must come from within the designated boundaries of Tsinandali, and must be dominated by Rkatsitelli, with 15% Khakuri Mtsvane allowed in the blend.

Mtsvane on the other hand, is a thinner-skinned white grape variety that has much more pronounced floral tones. It is a very successful blending partner to Rkatsitelli. This is particularly true in the wines from the region of Tsinandali, considered to be Georgia’s flagship white wine. While still bright and crisp, Tsinandali wines have an extra dimension of texture, intensity and floral lift not present in 100% Rkatsitelli wines. Tsinandali wines are not made in Qvevri, must come from within the designated boundaries of Tsinandali, and must be dominated by Rkatsitelli, with 15% Khakuri Mtsvane allowed in the blend.

Mtsvane itself is often used to make monovarietal wines in Qvevri, with a broader, open-knit palate as compared to the intensely textural Rkatsitelli. Other white varieties one encounters sporadically are Kisi, Khikvi, Tsolikouri, and Krakhuna.

Winemaking for the white wines made in the western style is typically straightforward. Regardless of grape, the wines are usually stainless steel fermented, and malolactic fermentation is blocked to retain the racy, crisp acidity. Some may be aged in oak barrels, though mostly the wines are rested in tank with light lees stirring and bottled young and fresh. Don’t mistake this for not having a capacity to age. Rkatsitelli is particularly age worthy, due to its high acidity, intensity, and textural components caused by its thicker skin.

If racy, brilliant wines are the norm for the whites, the red wines of Georgia couldn’t be at the farther end of the spectrum. Nearly all Georgian red wines are produced from the Saperavi grape.

If racy, brilliant wines are the norm for the whites, the red wines of Georgia couldn’t be at the farther end of the spectrum. Nearly all Georgian red wines are produced from the Saperavi grape.

Saperavi is a teinturier grape, meaning the veins of its flesh are red. This makes it impossible to make a white wine from Saperavi, no matter how gently the skins are pressed. The most famous teinturier grape most have heard of is Alicante Bouschet from Portugal. Like Alicante, Saperavi produces red wines deep with color and rich with tannins and intense flavors. These are wines which have all the components necessary to age and improve in the bottle.

Saperavi, which represented 30% of the total harvest in 2022 is made in a wide range of different styles. From fresh young wines with bright fruit flavors, to more serious expressions aged in French barriques and even semi sweet reds. Saperavi is also often made in Qvevri.

When bottled without oak aging, Saperavi displays flavors and aromas of fresh blackberries, mulberries, violets, a touch of black pepper and dried herbs. When aged in barrel, the wines naturally take on a more baked and jammy character to the fruit, with lots of cedary and tobacco tones mingled with espresso. The most serious and age worthy examples of Saperavi come from the fabled area of Mukuzani in the Khaketi region. Wines labeled Mukuzani must be made from 100% Saperavi and aged a minimum of three years in cask.

There is also a controlled appellation of origin for semi-sweet wines made from Saperavi : Kindzmarauli, in the region of Khaketi. Traditionally, most of this wine was exported to Russia, and it was extremely popular during Soviet times. It is still popular in Russia today. Taste wise, though the wine is sweet, it does have enough juicy acidity to keep it from being cloying. I like to describe it as a a darker, more structured and non-effervescent version of Brachetto d’Acqui. When made in this sweeter style, the pretty violet and iris floral tones are turned up to 11. It is a great pairing with spicy dishes, though care should still be taken with spice because the tannins are still present.

Though Georgia sits a world away from the rest of the wine world, the country’s pride and passion for its heritage is staggering. Its food, culture and grape varieties are not only unique, but diverse and delicious.

About the author: Evan Davis is a regional Wine Educator for Spec’s Wine, Spirits and Finer Foods in Austin, Texas. A classically trained chef, Evan cut his teeth working in some of Austin’s finest restaurants. His passion for wine blossomed through a passion for food, and a culinary exploration trip to the Napa Valley eventually sparked a full-on obsession and a career in wine.

Photo credits: Evan Davis

Great Job Evan! Very informative!!

Spot on Evan! Good information and I hope wine lovers will take the adventure and visit Georgia. Beautiful country, love the pride and passion of the people and live the wine!