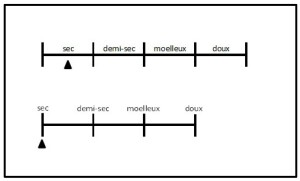

Here’s a newsworthy tidbit: beginning with the wines of the 2021 vintage, white wines produced under the Alsace/Vin d’Alsace AOC will be required to state their sweetness level on the label. This declaration may be narrative (using the terms sec, demi-sec, moelleux, or doux) or a graphic representation of a “sweetness scale.”

- The sweetness terms, which abide by general EU definitions, are as follows:

- Sec: 4 g/L sugar or less, or 9 g/L (or less) provided the level of tartaric acid is within 2 g/L of the amount of sugar

- Demi-Sec: 12 g/L sugar or less, or 18 g/L (or less) provided there is a minimum of 10 g/L of tartaric acid

- Moelleux: 45 g/L sugar or less

- Doux: More than 45 g/L sugar

This provision is not—yet—part of the rules and regulations for the Alsace AOC, although a proposal for a modification to the Cahier des Charges has been submitted to the INAO and was published in France’s Journal Officiel in June of 2021. Rather, it is now codified via its publication by the Direction Générale de la Concurrence, de la Consommation et de la Répression des Fraudes/DGCCRF of France (General Directorate for Competition Policy, Consumer Affairs and Fraud Control).

In the proposed modification of the appellation’s Cahier des Charges—now working its way through the legislative jungle—the new standard is applied under Article XII: Règles de Présentation et Étiquetage (Presentation and Labeling Rules), which state the following:

- Les vins blancs pour lesquels, aux termes du présent cahier des charges, est revendiquée l’appellation d’origine contrôlée “Alsace” ou “Vin d’Alsace,” à l’exception des mentions “Vendanges Tardives” et “Sélection de Grains Nobles,” qui sont présentés sous ladite appellation ne peuvent être offerts au public, expédiés, mis en vente ou vendus, sans que dans les annonces, sur les prospectus, étiquettes, factures et récipients quelconques, la mention de la teneur en sucre telle que définie par la règlementation Européenne ne soit inscrite le tout en caractères très apparents.

- Translated and paraphrased, this states the following: The white wines labeled under these specifications as “Alsace” or “Vin d’Alsace” [with the exception of those labeled as Vendanges Tardives or Sélection de Grains nobles] may not be offered to the public, shipped, offered for sale or sold without the mention of the sugar content (as defined by EU regulations) listed on all containers in very visible characters.

It should be noted that this new ruling applies only to the standard white wines (vins blancs) of the Alsace/Vin d’Alsace AOC, and does not apply to the appellation’s red wines, rosé, or wines labeled with the term vendanges tardives or sélection de grains nobles.

We’ll be keeping an eye out for the approval of the modified Cahier des Charges, but as any wine student knows…these things take time.

References/for more information:

- Modification to the Alsace AOC Cahier des Charges, as published in the Journal Oficiel on June 2, 2021

- proposed update to the Cahier des Charges for the Alsace AOC

- Regulations—Wines Alsace Sweetness Labeling—via the DGCCRF

Post authored by Jane A. Nickles…your blog administrator: jnickles@societyofwineeducators.org