Ask any wine student, and they will be eager to tell you: German wines are confusing. When you consider the combination of gothic-style script on labels, overlapping levels of the Prädikat, and a seemingly never-ending list of places-of-origin (only some of which are government-approved and therefore considered official)—most wine educators would agree.

Hang on to your hats, wine lovers, because the categorization and classification of German wines is about to change, and it is yet to be seen whether these changes will make the study of German wines easier, or even more (shall we say) complex.

Before we dive in, take heart: these changes are still in the works. While producers can implement the changes immediately, they are not required to do so until the 2025 vintage—and there is still quite a bit of regulatory work to be done. Nevertheless, here is what has been announced so far:

The hierarchy (and label terminology) for Prädikatswein—based on ripeness levels (must concentration) at harvest—will remain unchanged.

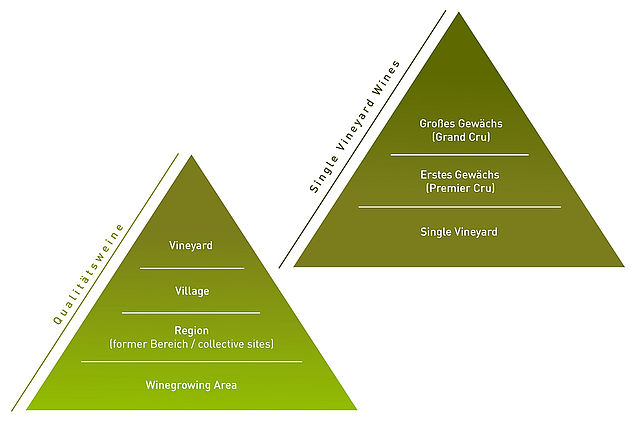

A new system (hierarchy)—based on geography and the philosophy of the smaller the area, the higher the quality—will come into force. This geography-based set of classifications will apply to PDO (protected designation of origin) wines only—both still and sparkling—and may be used for both Qualitätswein and Prädikatswein.

This geography-based hierarchy is not entirely new; current students of wine will recall the four levels of German wine place-of-origin categories—Anbaugebiete (area), Bereiche (region), Grosslagen (village), Einzellagen (vineyard)—currently in use. This new system changes the terminology up a bit, adds a few levels of specificity, AND allows for the regulation of grape varieties and wine styles at the higher levels. (Specific information on what these regulations will be is to-be-determined and is expected to be released over the next few months/years.)

Here is the new categorization of German wine place-of-origin terms, in order from largest (and—theoretically, less specific in qualifications and lowest in quality) to smallest (and—theoretically, with the most specific qualification and highest in quality).

- Anbaugebiet (area): This refers to Germany’s 13 quality wine regions (Anbaugebiete) and has not changed. Grapes may be grown in any part of the area, and the wine will carry the name of the area—such as Mosel, Rheinhessen, or Pflaz—on the label.

- Region: Each Anbaugebiet will be broken down in several specified areas (such as those previously referred to as Bereiche or Grosslagen). These regions will span several political areas such as communes or districts.

- Ortsweine (village): Named for a specific village; must reflect the typical grape varieties and wine style of the village. These wines must be produced from grapes harvested at least the Kabinett-level of ripeness and may not be sold before December 15 of the harvest year.

- Einzellage (vineyard): These wines must be produced in accordance with the grape varieties and wine styles typical of the vineyard. In addition, all wines at this level of the hierarchy (and above) must be made from grapes that are harvested at the ripeness/must concentration threshold as defined for the area’s Kabinett level grapes (or higher). The name of the Einzellage (vineyard) must appear on the wine label alongside the name of the region. These wines may not be sold before March 1 of the year following the harvest.

- Erstes Gewächs: This designation is made for a sub-plot of a vineyard and comes with a long list of qualifications, which may include specific grape varieties, methods of production, sensory characteristics, and limits on yield. This category is reserved for dry wines made from a single grape variety only. The quality level may be thought of as the “second-highest ranking” in the area, such as is reserved for Burgundy’s Premier Cru vineyards. These wines must be vintage-dated and may not be sold before March 1 of the year following the harvest.

- Grosses Gewächs: This designation may be considered the highest level in the category (similar to the Grand Cru vineyards of Burgundy). The qualifications are also steep—in addition to regulations on grape varieties, production methods, and sensory characteristics—the wine must be dry; and it must be produced from a single vineyard, a single grape variety, and a single vintage year. At this level, white may be sold after September 1st of the year following harvest, and red wines may not be sold until June 1st of the second year after harvest.

- Smaller plots of land known as Gewannen (singular: Gewann) may also be defined within the Erstes Gewächs or the Grosses Gewächs.

Side note: according to the press release linked below, “Associations that already use the terms Grosses Gewächs and Erstes Gewächs may continue to use them if they meet certain minimum requirements from the wine ordinance, for example with regard to grape varieties, yields, harvest regulations or the taste profile.”

Reference/for more information:

Post authored by Jane A. Nickles…your blog administrator: jnickles@societyofwineeducators.org