As many astute wine (and spirits) students are aware, the United Kingdom (UK) recently devised a specialized set of geographical indications (GIs) for use post-Brexit. Just like the larger EU-based scheme (which the UK is still eligible to participate in, if they so choose), the UK geographical indication scheme (administered by the UK’s Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs) aims to define and regulate specific products with the goal of protecting their name, authenticity, and characteristics.

As many astute wine (and spirits) students are aware, the United Kingdom (UK) recently devised a specialized set of geographical indications (GIs) for use post-Brexit. Just like the larger EU-based scheme (which the UK is still eligible to participate in, if they so choose), the UK geographical indication scheme (administered by the UK’s Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs) aims to define and regulate specific products with the goal of protecting their name, authenticity, and characteristics.

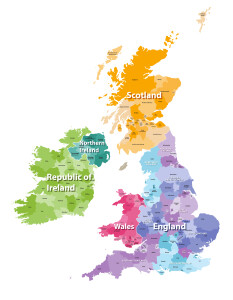

On July 24, 2023, Welsh Single Malt Whisky (Wisgi Cymreig Brag Sengl) was registered as a UK geographical indication. Welsh Single Malt Whisky is the twentieth product from Wales—a tiny country tucked between England and the Irish Sea—to gain this protected status. Other Welsh products so protected include Welsh Wine, Traditional Welsh Perry, Traditional Welsh Cider, Caerphilly Cheese, Anglesey Sea Salt, Welsh Lamb, Welsh Beef, and Welsh Leeks.

- According to the new standards, Welsh Single Malt Whisky GI must be produced according to the following specifications:

- It must be produced using 100% malted barley, Welsh water, and yeast (no other additives are permitted).

- All stages of the production process—from mashing, fermentation, distillation, and maturation to bottling—must occur in Wales.

- It must be distilled at a single Welsh distillery. Distillation must occur via the batch process, although the type and size of still is not mandated.

- It must be matured in wood barrels, in Wales, for a minimum of three years. The type, style, and age of the wood (and the barrel) is not specified.

- It must have a minimum alcoholic strength of 40% ABV.

- Note: The barley may be sourced from elsewhere, and malting does not need to occur within Wales. (Wales does, however, grow a good deal of barley.)

The product specification for Welsh Single Malt Whisky (as noted above) does not overly-specify any part of the production process, and as such, Welsh distillers are given the freedom to create unique expressions of the spirit. However, under the heading of “Organoleptic Characteristics” the regulations stress that Welsh Single Malt is intended to produce a whisky that “has a lightness of character not overwhelmed by excessive extract.”

Another portion of the product specification states that the rules are intended to allow producers to craft a “modern style of whisky…which is less oily and with a lack of grittiness and earthiness associated with more traditional whiskies.” Part of this is attributed to the “moderate Welsh climate” which can result in less overall evaporative losses and thus “enables the development of particular flavor (flavour) attributes.”

The application for the Welsh Single Malt Whisky GI was originally submitted in August of 2021 by the Welsh Whisky Association. At the time, the association was composed of five member distilleries, including Penderyn Distillery, Aber Falls Distillery, Dà Mhile Distillery, Coles Distillery, and In the Welsh Wind Distillery.

References/for more information:

Post authored by Jane A. Nickles…your blog administrator: jnickles@societyofwineeducators.org