Today we have a guest post from SWE member Jan Crocker, CSW. Jan, a current resident of southern California, earned her Certified Specialist of Wine (CSW) certification in 2016 and is currently studying for the Certified Specialist of Spirts (CSS). Wish her luck!

For more than a decade, the Santa Ynez Valley meant Pinot Noir and “Sideways” to wine and movie fans alike. With many of the film’s scenes shot inside The Hitching Post II steakhouse in nearby Buellton, restaurant-goers bemoaned the near-impossibility of getting a seat inside the eatery, let alone at its newly famous bar. Of course, customers lucky enough to secure a table ordered the wine that made the restaurant famous: Hitching Post “Highline” Pinot Noir.

During the 16 years after the release of “Sideways,” however, the valley has evolved into far more than a haven for bright, zesty Pinot Noirs and lively Chardonnays. It is now home to 120 wineries that produce 31 different varieties, with lesser-known grapes Lagrein, Cinsault, and Grenache Blanc thriving in the AVA’s vineyards alongside the more famous mainstays. Often thought to share the balmy temperatures of nearby Santa Barbara, its summer afternoons are surprisingly toasty, with the mercury often touching 90 degrees Fahrenheit – and its nights dropping to the low 50s, even at the end of July.

The Santa Ynez Mountains provide a rain shadow for the region, sealing in daytime sunshine and warmth that benefit Rhône varieties Syrah, Grenache Noir, Mourvèdre, Cinsault, and Viognier. Additionally, brisk late-afternoon winds and the sandy, largely infertile soils of the region’s lower elevations favor these classic grape varieties.

Two years ago, my husband and I were lucky enough to spend five lovely, warm summer days in Santa Ynez. We managed to visit seven wineries and three tasting rooms—Stolpman Vineyards, Dragonette Cellars, and Flying Goat Cellars. These three wineries are required to have their on-premise tasting facilities separate from their wine-production sites for a good reason—their vineyards are located well in the region’s inland reaches, near Happy Canyon and Ballard, where narrow, winding roads are the norm.

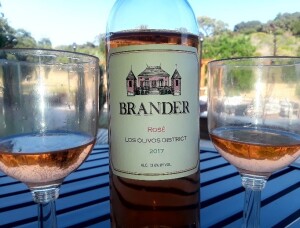

Although we found our way to wineries on the outskirts of the Foxen Trail—Brander Vineyard & Winery as well as Sunstone Winery come to mind—we gravitated toward the Rhône-esque wineries nearest Los Olivos, the tiny town roughly six miles from Buellton. Surprises and learning awaited us; my Pinot Noir-loving husband and yours truly, a fan of old-world Syrah to the core, both found selections we loved. Flying Goat’s Rio Vista Vineyards’ Pinot Noir spoke to his enjoyment of Dijon-driven Pinot Noirs, while I went weak in the knees over Melville Vineyards’ “Donna’s” Syrah, intensely soulful and brooding. Both of us discovered Koehler Winery—a site we has never heard about before—but have since been eager to suggest to wine fans.

Absolutely, we’ll return to the Valley over the next year or so, delighted to revisit our favorite wineries—and excited to explore new ones as they open.