Today we have a guest blog post from Elizabeth Miller, who takes a step back and looks at Vitis Vinifera from the “big picture” point of view. Read on – its very interesting!

Congratulations wine regions of America, you made it! You’ve graduated from being an emerging wine region and are now enjoying widespread commercial success and the respect you deserve.

How did you do it? By mastering Vitis vinifera.

In the American wine industry, vinifera is the new black. A wine lover might take this for granted, until he or she realizes the bounty of non-vinifera native grapes growing on the American land mass. Despite this, it seems that only through mastering the imported vinifera that a wine region earns commercial success and respect. I must ask: why does making it in America mean making vinifera?

Vinifera in a Land of ‘Other’

From sea to shining sea, the Lower 48 is a deluge of wine grapes, with the widest variety of wild grapes on the globe. Of the eight species of grapevines in the Vitis genus noted for wine, six are native to North America, while only vinifera is native to Europe. Despite the numbers game, the powerhouse species from across the pond is viewed as the most legitimate amongst all the grapevines in America.

The Path to Success

America is now producing more wine than ever, and wine is made in all 50 states. Since the 1960s the modern industry has been born anew and grown rapidly. In my research in preparation for an upcoming Society of Wine Educators webinar “Emerging Regions of the US”, a pattern became quite clear…

First, Vitis vinifera is planted in a young wine region. This decision is greeted with a mix of optimism and skepticism, and many people are dubious that vinifera can grow in a particular place or climate. Over time, viticulturists and winemakers learn about how vinifera interacts with a specific place, how best to cultivate it, and what authentic palate will be expressed from the region’s terroir. Then the magic happens! Articles are written, gold medals are bestowed, and the emerging region starts seeing sales in larger markets—first state, national, maybe even international!

Sometimes this path to success has a pioneer. In the 1800s, Agoston Haraszthy introduced many new vinifera varieties to California, and 125 of them are still found in California today, earning him the title “Father of Modern Viticulture in California.” We know how it turned out for California!

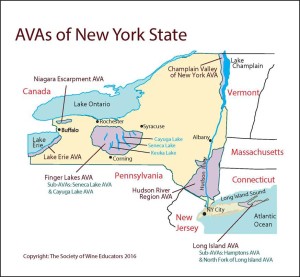

On the opposite coast, Dr. Konstantin Frank advocated for planting vinifera in the cold region of upstate New York in the 1960s, despite opposition. Riesling became an early winner. As I discussed in a recent Society of Wine Educators webinar, “I’m in a New York State of Wine”, the state rapidly grew and achieved national renown just a few decades later.

Many states are poised to leap into the limelight… with vinifera in hand. Grapevines have grown naturally in Texas along rivers and streams for thousands of years. The industry began on a commercial scale in the 1970s and today it’s ranked sixth nationally in number of wineries. The land bears one of the most diverse arrays of grapevines on earth, yet, the commercial industry is 99% vinifera!

What’s Going On?

To understand why the imported Vitis vinifera has emerged as the king in a sea of native species, we can look at several factors:

- Vinifera is tried and true. Humans are known to have interacted with vinifera as far back as the Neolithic period. The Latin root of the word literally means “wine-bearing.” The idiosyncrasies of making wine with vinifera have been fine-tuned for several thousand years. Physiologically, its skin thickness, sugar, alcohol content, and phenolic compounds make for a readily fermentable and universally palatable product.

-

American wine traditions came from Europe. The “old world” has been drinking wine and creating traditions for centuries. When European settlers came to the American continent, they brought their vinifera with them. While initial plantings of vinifera in the untested American climates resulted in many early failures, the sense of the superiority of vinifera as a wine grape remained. Traditions like the 1855 Bordeaux classification were in essence effective marketing schemes. They contributed to the sense that the apex of viticultural excellence reaches back to medieval Europe and Vitis vinifera.

- Other vitis species taste different. In the early days of American wine, settlers didn’t appreciate just how different American grapevine species were. They tried to make wine from the native grapes but found their flavors and textures off-putting and unfamiliar. Vitis labrusca, in particular was deemed “foxy”, and not in the good way. The early misunderstanding of native species left a lingering and tainted reputation, and today some consumers and sommeliers will not even pay a wine produced from a native grape variety.

- Native grape cultivation is fairly new. In the global race of grape cultivation, vinifera has a several thousand-year head start. In contrast, the identification of native grape species in America has only occurred in the last few hundred years. Due to the low demand for these native grapes, there is very little incentive to study them, and very few are in commercial cultivation. Until native grapes’ viticulture, vinification and styles are understood, only vinifera will be viewed as legitimate.

The Future of Vitis in America

Undeniably, Vitis vinifera has carried many American wine regions from obscurity to international fame. Yet, what might the Vitis scene be of the future?

Might an influential native grape emerge? A possibility could be Norton, a grape cultivar from Vitis aestivalis, grown widely through the Mid-Atlantic and Midwestern states. It has even begun to be grown in California. Norton’s cultivation dates back to the early 1800s, and it’s a candidate for a real contender on a global stage. It produces deeply-colored red wine with mouth-filling texture, ages very well, and has been compared to Zinfandel. It is also the cornerstone of the Missouri wine industry, whose current reputation pales in comparison to its pre-Prohibition standing when it was the second-largest wine-producing state in the nation! Could a non-vinifera grape like Norton find market power for itself and for Missouri?

Another thing to consider is what happens when Vitis vinifera fails. From the 1990s through the start of the millennium, the Colorado industry grew quickly. Its winemakers have enjoyed a growing reputation for Riesling and Cabernet Sauvignon. Unfortunately, that time also saw several fierce damaging freezes in a land of brutal winters, finicky springs, and some of the highest elevation vineyards in the Western hemisphere. Grape growers are now looking at more resilient hybrids which can produce great wines but are unfamiliar to Americans. Might a larger market embrace them, and then Colorado, in the future?

For the foreseeable future, though, Vitis vinifera is staying in style!

Elizabeth Miller is the General Manager of Vintology Wine & Spirits and the Associate Director the Westchester Wine School in Westchester County, NY. She will present a SWEbinar “Emerging Regions of the US” on Wednesday, December 7th, and 7:00 pm central time. Her blog ‘Girl Meets Vine’ is found at http://www.elizabethmillerwine.com/girlmeetsvine.

Are you interested in being a guest blogger or a guest SWEbinar presenter for SWE? Click here for more information!