This year has been rough in terms of wildfires in and around wine country. Most notably, harvest was interrupted in mid-September by the third in a series of devastating wildfires around Lake County.

As such, we’ve had quite a few questions directed our way about how this might affect the wines of the regions affected by these fires. We’ve all heard of smoke taint – so is this something we need to be worried about?

It is a relatively new area of study – in 2003, wildfires in Eastern Victoria, Australia motivated researchers to begin studying the chemical backdrop and the variables associated with this increasingly dangerous phenomenon. The Australian Wine Research Institute (AWRI) and Washington State University (WSU) have led the way in publishing the most up-to-date and applicable research on this topic. Although much of this research is geared toward the winemaker/ producer, it is of interest to wine educators and other wine professionals as well.

For starts, smoke taint is the general term given to a host of volatile phenols, with the most important being as follows:

- Guaiacol (smoky)

- 4-methylguaiacol (spicy)

- Eugenol (clove)

These same phenolics can be introduced into wine via ageing in heavily toasted oak. Typical recognitions thresholds for these molecules are quite low; we can pick out the “ashtray” and “camp fire” aromas at concentrations as low as 23-27 micrograms/L or parts per billion (ppb).

Complications can arise due to the fact that these molecules can be present in a wine in bound form, meaning the smoky character may not reveal itself until after alcoholic fermentation, malolactic fermentation, or even after extended bottle ageing. In addition, once this smoky character shows, it will always intensify with time in the bottle.

Studies concerning smoke in the vineyard have so far been inconclusive, and have yet to determine the minimum exposure time and concentration of smoke that vines can tolerate before it noticeably affects the wine. However, it is known that the flavors collect in the skins and the flesh just below the skin in addition to translocating from the leaves. This greatly influences winemaking techniques once the fruit is brought into the winery.

When – in the growing cycle – the vines are exposed to smoke has proven to be one of the most important factors in pin-pointing the risk. The AWRI has identified three categories for the sensitivity and likelihood of smoke uptake throughout the growing cycle:

- During and before flowering there is little risk;

- From early fruit set to three days post-verasion there is low to medium risk;

- Post-verasion to harvest there is high risk.

It has also been proven that there is no risk to carry over smoke taint from one growing season to the next, and that the smoke character does not vary with smoke from different types of wood or fuel. Studies originally showed that the smoke uptake varied by variety, with Merlot and Sangiovese being more susceptible. However, recent studies under controlled conditions have shown that variety does not matter.

Berries and wine can be tested for levels of smoke taint, and there are several techniques that can be implored to minimize the effects. These include the following:

- First and foremost, fruit must be hand harvested and leaves must not enter the fermentation vessel.

- Skin contact must be limited, as this is where the volatile compounds are found.

- Cold soak, extended maceration, and aggressive pressing should be avoided.

- Fruit must stay as cold as possible.

- Reverse osmosis is often used to reduce smoke taint, but has been found to be not entirely reliable as it does not address the “bound” form of the chemicals.

- Other techniques such as aggressive filtering are useful to a degree, but need to be used with caution in order to avoid stripping the wine of desirable flavors as well as the unwanted smoky character.

- There is some anecdotal evidence that the use of flash détante may allow guaiacol to volatize and burn off.

Most wineries will keep the tainted wine separate, then either blend back in a declassified wine program, or bottle separately marketing the wine as having a smoky character – which some customers appreciate.

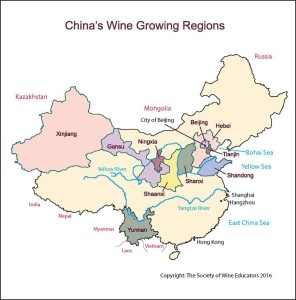

As drought becomes more endemic in a variety of wine regions around the world, the risk for smoke infected wine – and its financial impact on the wine industry – is on the rise as well. As industry professionals, we must be aware of the regions and vintages where there was a verified risk of smoke taint. These include:

- Victoria, Australia: 2003 and 2007 were devastating, and 2009 saw traces of smokiness. 2008 in Mendocino County, California: Effects were noticeable in 2008

- Washington State: 2012 and 2015 were fiery years for Washington State, particularly the Lake Chelan AVA

- Lake County: Most recent, and near to our hearts, 2015 saw harvest interrupted and substantial damage to vineyards around Guenoc. Thankfully, it appears that the major growing areas around Clear Lake were spared.

We’ll keep trying to learn more and lessen the likelihood that wild fires will taint our wine. In the meantime, we’ll trust our favorite winemakers and producers not to put defective wine in the bottle.

References:

- https://www.awri.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Adelaide_Hills_Smoke_AWRI.pdf

- http://wine.wsu.edu/research-extension/2012/09/smoke-taint/

- https://www.etslabs.com/resources/publications/analytical-tools-for-harvest/smoke-taint.aspx

- https://www.etslabs.com/resources/publications/oak-aroma-analysis/technical-bulletin—ets-oak-aroma-analysis.aspx

Post authored by Mark Rashap, CWE. Mark has, over the past ten years, been in the wine world in a number of capacities including studying wine management in Buenos Aires, being an assistant winemaker at Nota Bene Cellars in Washington State, founding his own wine brokerage, and working for Texas-based retail giant Spec’s as an educator for the staff and public.

Post authored by Mark Rashap, CWE. Mark has, over the past ten years, been in the wine world in a number of capacities including studying wine management in Buenos Aires, being an assistant winemaker at Nota Bene Cellars in Washington State, founding his own wine brokerage, and working for Texas-based retail giant Spec’s as an educator for the staff and public.

In August of 2015, Mark joined the team of the Society of Wine Educators as Marketing Coordinator to foster wine education across the country.

Are you interested in being a guest blogger or a guest SWEbinar presenter for SWE? Click here for more information!