The area around the Mediterranean Sea, home to miles of sun-drenched beaches, mild winters, olive groves and (of course) fabulous wine, has been a cultural crossroads since the dawn of civilization. The beautiful weather, with the four seasons seemingly compressed into two, is surely one of the major reasons why so many people decided to make this region their home.

The area around the Mediterranean Sea, home to miles of sun-drenched beaches, mild winters, olive groves and (of course) fabulous wine, has been a cultural crossroads since the dawn of civilization. The beautiful weather, with the four seasons seemingly compressed into two, is surely one of the major reasons why so many people decided to make this region their home.

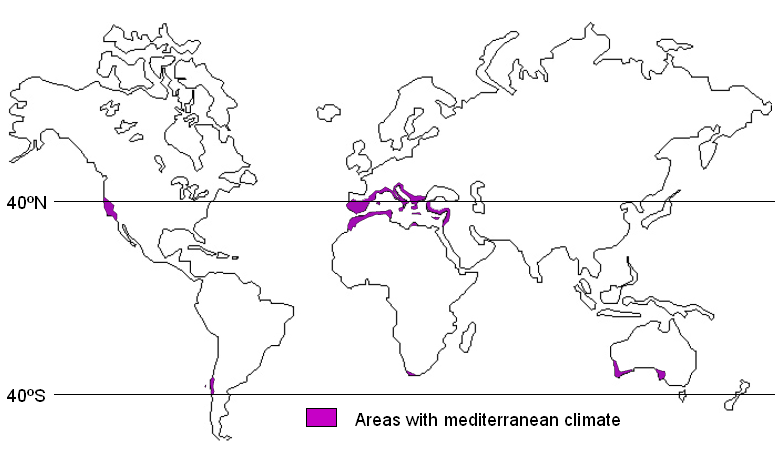

The comfortable climate typical of the Mediterranean Basin is found in many other areas throughout the world, including California and Baja California, the Central Coast of Chile, Southwest and South Australia, and the Western Cape Region of South Africa. We serious students of wine will easily recognize these areas as major wine producers, and, of course, areas blessed with a Mediterranean Climate.

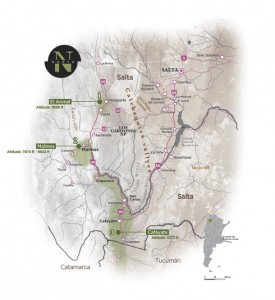

The Mediterranean Climate, known as a “dry-summer subtropical” climate under the Köppen climate classification, is generally found between 31 and 40 degrees latitude north and south of the equator, on the western side of continents. The climate can be summarized as “warm, dry summers and mild, rainy winters.” The climate zone can extend  eastwards for hundreds of miles if not thwarted by mountains or confronted with moist climates, such as the summer rainfall that occurs in certain regions of Australia and South Africa. The furthest extension of the Mediterranean Climate inland occurs from the Mediterranean Basin up into western Pakistan. In contrast, areas of California and Chile are constricted to the east by mountains close to the Pacific Coast.

eastwards for hundreds of miles if not thwarted by mountains or confronted with moist climates, such as the summer rainfall that occurs in certain regions of Australia and South Africa. The furthest extension of the Mediterranean Climate inland occurs from the Mediterranean Basin up into western Pakistan. In contrast, areas of California and Chile are constricted to the east by mountains close to the Pacific Coast.

The oceans and seas bordering the land areas with a Mediterranean climate work their moderating magic and keep the temperatures within a comparatively small range between the winter low and summer high. Snow is seldom seen and winters are generally frost-free. In the summer, the temperatures range from mild to very hot, depending on distance from the shore, elevation, and latitude. However, as anyone who has experienced Southern California’s Santa Ana Winds will tell you, strong winds from inland desert regions can bring a burst of dry heat to even the mildest season.

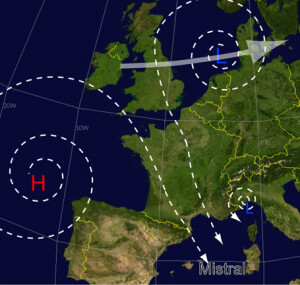

In addition to the influence of water, specific atmospheric conditions create the Mediterranean climate. Every area that enjoys a Mediterranean Climate is located near a high pressure cell that hovers over the ocean or sea. These high pressure cells move towards the poles in summer, pushing storms away from land. In the winter, the Jet Streams shift the cells back towards the equator, drawing stormy weather inland.

In addition to the influence of water, specific atmospheric conditions create the Mediterranean climate. Every area that enjoys a Mediterranean Climate is located near a high pressure cell that hovers over the ocean or sea. These high pressure cells move towards the poles in summer, pushing storms away from land. In the winter, the Jet Streams shift the cells back towards the equator, drawing stormy weather inland.

The long, dry summers of the Mediterranean Climate zones limit plant growth for much of the year, so the natural vegetation of such areas has adapted into evergreen trees such as Cypress and Oak as well as shrubs such as Bay Laurel and Sagebrush. Trees with thick, leathery leaves and protective bark such as olive, walnut, citrus, cork oak, and fig are also abundant; and as those early settlers in the Mediterranean Basin figured out—grapevines thrive here as well.