Today we have a guest post from Houston-based Wine Educator James Barlow, CS, CWE – all about some modern wines from a most ancient place…the Greek Island of Santorini.

Today we have a guest post from Houston-based Wine Educator James Barlow, CS, CWE – all about some modern wines from a most ancient place…the Greek Island of Santorini.

When one thinks of Greece, one might envision the great Greek Gods – Dionysus, Zeus, and Apollo – sipping wine from golden goblets, perched on high watching the humans battle in epic duels.

When one thinks of Greek wine, one might envision pine resin and retsina – and this has often kept people from delving much farther into the world of Greek wines.

However, Greek wine is so much more! Greece is home to some of the more interesting indigenous grape varietals on earth. Smoky, bone dry whites such as Assyrtiko or full bodied reds such as Mavrotragano and the deliciously sweet Vinsanto are truly the “nectars of the Gods.”

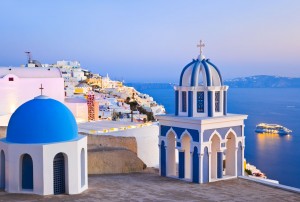

Vines have been grown in Greece for centuries, but in the modern world, Greek wines have been widely overlooked by the wine community. However, the small island of Santorini, located in the southern Cyclades Islands, is looking to change the way the world looks at the wines of Greece.

The History and Geography of Santorini

The History and Geography of Santorini

First, a bit of history about Santorini, which will give a better understanding why this small island has excellent terrior and climate to cultivate vines. Santorini was the core of an ancient volcano that erupted in about 1640-1620 BC. This submerged a large part of the island and created a caldera where the center of the island had been. The result was a unique mix of chalk and shale beneath ash, lava and pumice, which contributes to the vines having to struggle deep into the soil to find nutrients.

This, in turn, gives the resulting wines intense minerality and singularity in the wine world. It also is the core reason why the root louse, phylloxera, has never become an issue on this small island. This fact allows Santorini to have many old vine vineyards. Grapes are grown on the eastern edge of the caldera at nearly 1,000 feet in altitude. To add even more stress to the vine, Santorini sees almost no rain during the growing season and the vines only source of water comes from the early morning fog condensation that covers the island. This is enough to keep the vines alive and thriving.

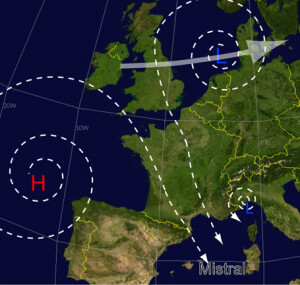

Steady westerly winds keep the grapes from seeing much of the condensation thus eliminating any chance of rot. In fact, the winds are so fierce that the vines are typically trained to grow in a Stefani shape, a round basket, where the middle is left open for the clusters of grapes to grow unimpeded.

Assyrtiko: Rich, Mineral-driven Whites

Assyrtiko: Rich, Mineral-driven Whites

It is in this environment on Santorini that Greece’s most intriguing white grape is grown. Assyrtiko (A seer’tee ko) might just become the next “darling” white wine for sommeliers and wine critics alike. The varietal is often referred to as ‘the white grape in red’s clothing’. It is a high acid, full-bodied white with moderately high alcohol that gives the consumer a chance to taste the essence of Santorini.

The minerality that the grape inherits from the soils is sky high. Flavors of crushed rocks and smoky minerals meld into the bone dry acidity while maintaining ripe citrus fruits such as melon, apple and key lime. Assyrtiko will be sometimes be blended with small amounts of Athiri and Aidani to add aromatics to the bracing acids. The wine may sometimes see oak, but is typically aged in stainless steel vats. Wild yeasts are usually used in fermentation which gives the ensuing wine unique character and flavor profile. Santorini has 70% of its vines dedicated to this variety. Some of the best examples are done by Gaia, who produces an unbelievably good wild ferment, and Paris Sigalas.

Vinsanto from Santorini

Assyrtiko(minimum 51%) and Aidani are also the main grape varieties used for the passito-style Vinsanto dessert wines. The late harvested grapes are left out on straw mats for 1-2 weeks which causes them to concentrate and raisinate. The grapes then go through a  lengthy fermentation process then are aged in oak casks for a minimum of 24 months, but usually for much longer. The ending results are deliciously sweet wines with flavors of matured honey, dried apricots, and molasses.

lengthy fermentation process then are aged in oak casks for a minimum of 24 months, but usually for much longer. The ending results are deliciously sweet wines with flavors of matured honey, dried apricots, and molasses.

The wines are typically low in alcohol and high in sugar, yet are not cloying due to the vibrant acidity of Assyrtiko. Vinsanto of Greece, not to be confused with Vin Santo of Tuscany, now has the exclusive rights to the name ‘Vinsanto’ although Tuscany can still use the name on the label to describe the ‘style’ of wine making. Vin meaning wine, Santo short for Santorini…Vinsanto. Makes sense.

Mavrotragano: Big, Bold Red

Santorini may be best known for its indigenous white varietals, but the reds are beginning to make head way in the market. Mavrotragano is the red grape that is making the biggest waves. This rare, indigenous variety produces small, thick skinned grapes of very low yield. Due to the lack of phylloxera issues, this varietal remains largely on its original rootstock. Mavrotragano was nearly extinct before being resurrected by Haridimos Hatzidakis and Paris Sigalas to critical acclaim. The wine is aged for a minimum of 1 year in oak, usually French. The flavor profile is reminiscent of Nebbiolo with red fruits, large notes of minerality and full, yet supple tannins.

The complex, indigenous varietals of this small, yet uniquely gifted island is leading the resurgence of Greek wine in the world. Greece is leaving the tarnish of Retsina in the past and forging forward with its indigenous quality varietals and the island of Santorini leading the way.

Our guest author, James Barlow, CS, CWE, is a wine director of over 6,000 wines labels for a store owned by Spec’s Fine Wines and Liquors in Houston, Texas. He is also the author of the widely recongized wine blog thewineepicure.com. James is also a recent recipient of the CWE Certification (Congratulations, James!) and as such has taken on the duty of teaching the Certified Specialist of Wine course to fellow employees in hopes of having the best educated staff in the state of Texas. Way to go, James!

Our guest author, James Barlow, CS, CWE, is a wine director of over 6,000 wines labels for a store owned by Spec’s Fine Wines and Liquors in Houston, Texas. He is also the author of the widely recongized wine blog thewineepicure.com. James is also a recent recipient of the CWE Certification (Congratulations, James!) and as such has taken on the duty of teaching the Certified Specialist of Wine course to fellow employees in hopes of having the best educated staff in the state of Texas. Way to go, James!

Click here to return to the SWE Website.

![9.8-The-Haut-Medoc-4-color-[Converted]](http://winewitandwisdomswe.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/9.8-The-Haut-Medoc-4-color-Converted-231x300.jpg)