.

It’s such a great question for a wine exam…it might be worded something like this: “Which of the following regions all produce sparkling wine under a Crémant AOC?” The answer could include the following names: Alsace, Bordeaux, Bourgogne, Jura, Limoux, Die, Savoie, and the Loire.

As wine lovers, we all acknowledge there is (and will always be) only one Champagne, but we also know that many sparkling wines are produced in France—and some of these sparkling wines are entitled to use the term “Crémant” in the context of their AOC pedigree.

These crémants have a lot in common— the most important principle being that they must be produced using the Traditional (bottle-fermented) Method of sparkling wine production. In addition, they must all be aged for a minimum of 12 months post-tirage—including at least 9 months on the lees—and hand-harvesting is mandatory. Beyond these basics, however, there is quite a bit of diversity in the crafting of crémant. Read on to find a few of these differences…you may find a new favorite wine, and you may glean some information that could prove to be useful on your next wine exam!

Christmas time at the Place Kléber in Strasbourg

Crémant d’Alsace: Among students of wine, the Crémant d’Alsace AOC is remembered for being the only AOC in the region to allow the use of the Chardonnay grape (although Pinot Blanc is more likely to be found in your flute). Bubbly from Alsace is unique in that it allows for the use of an interesting array of grapes: white sparklers may be made using Riesling, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris, Auxerrois, and/or Chardonnay; rosé (more typically) must be 100% Pinot Noir.

Crémant d’Alsace makes up a good proportion of the total output of wines from Alsace and typically accounts for anywhere from 20% to 25% of the total output of the region. These wines are widely distributed and relatively inexpensive. I often pick up a bottle of Lucien Albrecht Crémant d’Alsace Brut N/V at my local “fancy” grocery store ($21.99 the last time I checked); this is a lovely, delicate wine with floral notes and fruity (apple, peach, pear, apricot) flavors made from 50% Pinot Blanc, 25% Pinot Gris, and 25% Riesling.

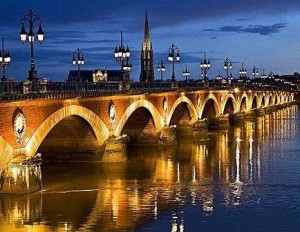

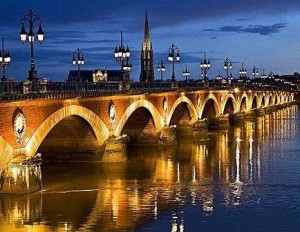

The Pont de Pierre (“stone bridge”) over the Garonne River in Bordeaux

Crémant de Bordeaux: Just a tiny bit of Crémant de Bordeaux is produced, particularly when you compare the 250 acres (110 ha) dedicated to producing Bordeaux bubbles—as compared to 300,000 acres (110,000 ha) for the whole region. However, the bubbly version is allowed to be produced anywhere within the confines of the larger Bordeaux AOC, so larger quantities are possible.

Crémant de Bordeaux is allowed to be produced using the standard grapes of the area—with a required minimum of 70% of the blend dedicated to Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Malbec, Petit Verdot, Carmenère, Muscadelle, Sémillon, Sauvignon Blanc, and Sauvignon Gris. The other 30% may also contain Colombard, Merlot Blanc, and/or Ugni Blanc. Crémant de Bordeaux may be white (blanc) or rosé.

Some of these wines make it to the US, and I’ve recently enjoyed Jaillance Cuvée “L’Abbaye” Crément de Bordeaux Sparkling Brut—a crisp, clean, fruity blend of 70% Sémillon and 30% Cabernet Franc, purchased for around $17.00

.

Crémant de Bourgogne: Crémant de Bourgogne may be produced anywhere within the Bourgogne wine region, and is often noted as a “replacement” wine for Champagne—for a few very good reasons. First, a good deal of the grapes used in Crémant de Bourgogne are grown in the Châtillonnais, in a group of vineyards clustered around the town of Châtillon-sur-Seine, located very close to the Aube department (and the southern boundary of the Champagne region).

In addition, the list of grapes allowed are similar (although not identical, as nothing in the world of wine is ever that simple) to those used in Champagne—including Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc, Aligoté, Melon de Bourgogne, Sacy (a white grape also known as Tressallier), Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris, and Gamay. The final blend is required to contain a minimum of 30% (combined) Chardonnay, Pinot Gris, Pinot Blanc, and/or Pinot Noir; and Gamay is topped at a maximum allowance of 20%. Crémant de Bourgogne may be either white or rosé.

These wines are usually easy to find in the larger US Markets; I often pick up Simonnet-Febvre Brut N/V Crémant de Bourgogne at my local “big box” wine and spirits store. This sparkler, produced from a traditional-sounding blend of 60% Chardonnay and 40% Pinot Noir, is aged for 24 months on the lees. The result is an elegant wine with aromas and flavors of citrus, apple blossoms, green apples and brioche.

.

Crémant de Die: Crémant de Die AOC is one of a group of AOCs—also including Châtillon-en-Diois, Coteaux de Die, and the slightly-sweet-and-slightly-bubbly Clairette de Die—located in the Drôme Département to the east of the Rhône River (and, latitudinally speaking, somewhat in-between the Northern and Southern Rhône).

Crémant de Die is only produced in a white (blanc) version, and must have no more than 1.5% residual sugar. Crémant de Die is typically based on the Clairette grape, with allowed inclusions of Aligoté as well as a maximum of 10% Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains.

Crémant du Jura: The Jura—known to most wine lovers as that obscure region between Burgundy and Switzerland—is recognized in particular for its biologically-aged Vin Jaune and its fortified MacVin du Jura. However, Traditional Method sparkling wines—both white and rosé—have been produced under the Crémant du Jura AOC since 1995. Still wines produced in the same area are labeled under the Côtes du Jura AOC.

The grapes allowed in Crémant du Jura include Pinot Gris, Pinot Noir, Poulsard (a dark-skinned red grape), Trousseau (a red grape also known as Bastardo), Chardonnay, and Savagnin.

The Château de Chenonceau in the Loire Valley

Crémant de Loire: The Crémant de Loire AOC is considered to be a regional appellation of the Loire Valley, and while it is (along with Rosé de Loire) about as close as the area gets to a regional appellation, the bubbly wine is only allowed to be produced in the center part of the long and winding Loire Valley (equating to those areas covered by Anjou, Saumur, and Touraine).

Crémant de Loire may be produced in white and rosé versions. The list of approved grapes reads like the greatest hits of the Central Loire, and includes Chenin Blanc, Chardonnay, Orbois, Grolleau, Grolleau Gris, Pinot Noir, Pineau d’Aunis, Cabernet Sauvignon and/or Cabernet Franc. Of these varieties, Cabernet Franc and/or Cabernet Sauvignon are restricted to a maximum of 20% of the final blend.

Crémant de Limoux: Sparkling wines produced in the Languedoc have been bottled under the Crémant de Limoux AOC since 1990. These wines are probably going to remain less popular and less well-known than their cousins bottled under the terms Blanquette de Limoux or Vin Mousseux Blanc Méthode Ancestrale (part of the Limoux AOC). Crémant de Limoux wines have their own style, and are typically produced drier, aged longer, and always produced using the Traditional Method—as opposed to their more famous cousins. Crémant de Limoux, which may be white or rosé, is produced using 50% to 90% Chardonnay, 10% to 40% Chenin Blanc, and allows for limited use of Mauzac and Pinot Noir.

Crémant de Savoie: Crémant de Savoie is the new kid on the block, having been approved as an appellation (separate from the overarching Savoie AOC) in 2021. Savoie is known for featuring unique grape varieties, and their bubbly is no exception: the assemblage must contain a minimum of 40% Jacquère, and an additional 20% must be Jacquère or Altesse only.

References/for more information:

Post authored by Jane A. Nickles, CSE, CWE…SWE’s Director of Education and Certification

Tucked alongside the massive La Mancha DO, Manchuela is a fairly large, landlocked wine region poised on the eastern edge of Spain’s comunidad autónoma Castilla-La Mancha. Manchuela is, in many ways, similar to the La Mancha DO and was previously part of the larger region. However, in 2000 the DO split off to forge its own identity. The name reflects this history: Manchuela, literally means “lesser La Mancha” or “little La Mancha.”

Tucked alongside the massive La Mancha DO, Manchuela is a fairly large, landlocked wine region poised on the eastern edge of Spain’s comunidad autónoma Castilla-La Mancha. Manchuela is, in many ways, similar to the La Mancha DO and was previously part of the larger region. However, in 2000 the DO split off to forge its own identity. The name reflects this history: Manchuela, literally means “lesser La Mancha” or “little La Mancha.” White wines may be produced using an impressive list of grapes, which includes Macabeo (Viura), Albillo Real, Chardonnay, Moscatel de Grano Menudo (Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains), Pardillo, Sauvignon Blanc, Verdejo, and Viognier. The white wines of the Manchuela DO are produced in several styles, including young, aged, oak-fermented and aged in oak. Recently, the appellation approved vino brisado for production in the area as well.

White wines may be produced using an impressive list of grapes, which includes Macabeo (Viura), Albillo Real, Chardonnay, Moscatel de Grano Menudo (Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains), Pardillo, Sauvignon Blanc, Verdejo, and Viognier. The white wines of the Manchuela DO are produced in several styles, including young, aged, oak-fermented and aged in oak. Recently, the appellation approved vino brisado for production in the area as well.