Today we have a guest post from Kate Brandt. While Kate was a student in my CSW online prep class, she mentioned on our class forum that the winery where she worked—Ampelos Cellars—was the first vineyard in the US to be “triple certified” organic, biodynamic, and sustainable. I was fascinated by her story and asked if she would like to write a blog post about the company. Lucky for us, she agreed, and we are so thankful to have Kate tell us this fascinating tale!

The Story of Ampelos Cellars, by Kate Brandt

As a Navy Spouse, I have had the opportunity to travel all over the world and visit some amazing places. While living in Italy, I visited a small, 7-generation, family owned, organically farmed vineyard. It was there I had my ‘A-HA’ wine moment and knew I wanted to spend the rest of my life learning about wine. It wasn’t until eight years later, when our family was stationed at Vandenberg Air Force Base in Central California that I got that opportunity … when I started working for Ampelos Cellars.

Peter and Rebecca Wonk

Owned and operated by Peter and Rebecca Work, Ampelos Cellars is the first vineyard in the United States to be triple certified Organic (USDA CCOF Organic), Biodynamic (Demeter) and Sustainability in Practice (SIP). Located in the beautiful Santa Rita Hills wine region, Ampelos Cellars focuses on creating minimally invasive wines that tell a fantastic story about the soil and vines, making it easy for the consumer to enjoy the wines while creating their own great memories and stories to tell.

Peter and Rebecca bought their property in 1999 for a future a retirement project. What a great and romantic dream, to wake up in the morning and have coffee while watching their dogs run through the vines, right!? Then, a series of cancelled meetings following the 9/11 World Trade Center attack had them thinking they were done with the corporate world. They pushed up their retirement dream and started in making wine full time. In 2001, they planted their first vines – Pinot Noir, Syrah, Grenache and Viognier. In 2004, they harvested their first 15 acres, and, in 2006, they converted their vineyard to organic and biodynamic farming. They achieved their SIP certification in 2008, and their organic and biodynamic certifications in 2009.

.

But what do all these certifications mean to the world of wine?

Organic Farming: Simply put, the main concept of organic farming is zero impact on the environment.

Organic farming follows standards for the use of natural fertilizers such as compost manure and biological pest control such as ladybugs and chickens instead of synthetic pesticides. Also, organic farming uses techniques such as crop rotation, cover cropping and reduced tillage. This exposes less carbon to the atmosphere resulting in more soil organic carbon. All of these practices are aimed to protect the earth, thus feeding the soil to feed the plant.

.

Biodynamic Farming: Biodynamic farming was originally introduced in 1924, when a group of European farmers approached Dr. Rudolf Steiner (noted scientist, philosopher, and founder of the Waldorf School) after noticing a rapid decline in seed fertility, crop vitality and animal health.

Quartz crystals are buried in female cow horns because they are made of silicon which add more nutrients to the soil

It was the first of the organic agricultural movements when an English Baron, Lord Northbourne, coined the term “organic farming”, and the concept of “farm as an organism” was adapted. It has similar ideas to organic farming in that it practices soil fertility and plant growth. However, there is a larger emphasis on spiritual and mystical perspectives such as choosing when to plant, cultivate or harvest crops based on phases of the moon or zodiac calendar.

Some biodynamic compounds used include:

- Cow manure sprayed in the soil — Stimulates soil structure, humus formation, bacteria, soil life, fungi and brings energy and vitality to the roots. This regulates levels of limestone and nitrogen in the soil and increases water holding capacity of the soil.

- Silica (quartz crystals) sprayed on the foliage — Allows leaves, shoots and clusters to enhance their use of light and heat. It improves photosynthesis, and assists with the plants assimilation of atmospheric forces.

- Yarrow added to the compost pile — Attracts trace elements of sulfur and potassium, aiding plant growth.

.

Sustainability In Practice: While Organic Certification only addresses the prohibition of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, SIP addresses the whole farm by looking at how the farmer gives back to the community, environment and business. The main goal is to help ensure both natural and human resources are protected.

There are 10 areas of SIP practices. Examples include:

- Conservation and Enhancement of Biological Diversity — enhances and protects a biologically diverse agricultural ecosystem while maintaining productive vineyards.

- Vineyard Acquisition/Establishment and Management — focuses on the decisions affecting the vineyard’s ability to sustainably produce high quality fruit with minimum inputs and manipulations.

- Soil Conservation and Water Quality – focuses on protecting the resources necessary for plant life including land, soil, and water.

- Pest Management – focuses on pest management rather than pest control, including controlling weeds, root insects, canopy insects, and diseases.

Chickens used for pest control and natural

fertilizer to the soil

Differences between the main farming practices:

- Conventional

- Get the biggest yields possible

- Spray artificial pesticides and fertilizers

- Quick profitability

- Organic

- Does not spray artificial pesticides or fertilizers

- Does not focus on other farming aspects (energy, fertilizer, water conservation, etc.)

- Biodynamic

- Treats the whole ranch as one system; everything is in balance with Mother Nature

- Waste of one thing is the energy for something else.

- Sustainability In Practice

- Focuses on energy, employee practices, water conservation, for example

- Breaks farming down into 10 areas (some listed here): energy, water conservation, social equity, pest management, etc.

Ampelos is the Greek word for vine. Peter and Rebecca named the winery Ampelos because they believe every great wine begins with the vine and health of the vineyard. They have successfully achieved their dream of creating well-crafted, clean, natural wines through eco-friendly wine making. When I was in Italy, I realized I wanted to start a journey of my own in the wine industry. I had no idea then my journey would bring me full circle to a family-owned, triple-certified vineyard. I am lucky to learn from Peter and Rebecca and benefit from their experiences with every bottle I share as I continue on my voyage of wine with a full glass!

About the author: Kate Brandt is a proud Navy spouse and mother of two energetic girls. She loves to travel, learning about (and drinking) wine, and enjoying treasured friendships.

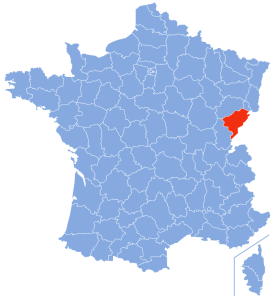

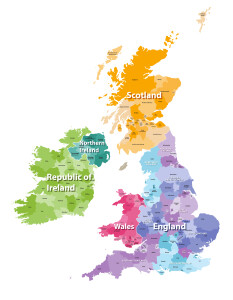

As many astute wine (and spirits) students are aware, the United Kingdom (UK) recently devised a specialized set of geographical indications (GIs) for use post-Brexit. Just like the larger EU-based scheme (which the UK is still eligible to participate in, if they so choose), the UK geographical indication scheme (administered by the UK’s Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs) aims to define and regulate specific products with the goal of protecting their name, authenticity, and characteristics.

As many astute wine (and spirits) students are aware, the United Kingdom (UK) recently devised a specialized set of geographical indications (GIs) for use post-Brexit. Just like the larger EU-based scheme (which the UK is still eligible to participate in, if they so choose), the UK geographical indication scheme (administered by the UK’s Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs) aims to define and regulate specific products with the goal of protecting their name, authenticity, and characteristics.