.

Today we have a guest post from Elizabeth Yabrudy, CSS, CSW, CWE. Elizabeth is a member of SWE’s Board of Directors and a wine professional who recently move to Uruguay. In this informative post, she brings us up to date on the dynamic world of Uruguayan wine.

“A glass of Albariño, please!”

I just asked for it when I sat down in the hall of Iberhouse, the new concept of Iberpark, one of the most important liquor stores in Montevideo. And yes, I am in Uruguay’s capital city, wishing to drink a glass of Uruguayan Albariño. If you are surprised, you haven’t been paying attention to what the wine world has said lately about this small but amazing wine country.

I have been following the wines of Uruguay since 2000. Over the years I have tasted some good— and some not so good—wines, but also some incredible jewels. For quite a while, the wines of Uruguay were all about Tannat (varietals and blends), always powerful wines, full of tannins and flavor. At the beginning, I would say until 2010 or maybe a little later, this industry was talking solely about this French grape that turned to be the iconic grape of Uruguay.

.

But the Uruguayan wine industry is now so much more than just Tannat. It has evolved in a beautiful way. Now you find a country that offers different profiles of Tannat (talking not only about vinification, but also about a sense of place), excellent whites which have made Albariño the superstar, and a great portfolio which includes other varieties like the less known Arinarnoa and Marselan, but also excellent Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Pinot Noir, Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Viognier, and so many others.

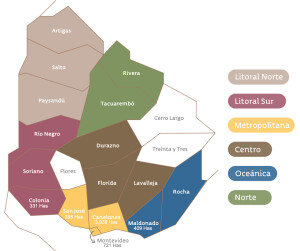

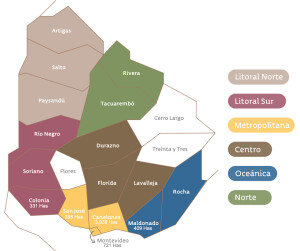

According to the official data from Inavi (National Institute of Viticulture), there are around 6,000 hectares of cultivated area, more than 1,180 vineyards located in 17 of the 19 departments of Uruguay, and plus 860 producers. This year (2023) Uruguay produced around 70.000.000 kilograms, as indicated by Eduardo Felix, Inavi’s Technical Advisor. This is less than the last official data published (2022) when it was registered a production of 102.616.440 kilograms, and this is mainly due to the drought that the country has been experiencing. Felix appointed during our phone interview, that 30% goes to the export market (Brazil and the United States are the most important markets, followed by England, Canada, Mexico, Sweden and Finland), and the rest is consumed locally. They are expecting this percentage to increase.

As an interesting fact, Marcos Carrau -Production Manager at Bodegas Carrau and a member of the 10th generation of Carrau’s Family- tells that when his grandfather started his export project in the 70s, it was considered of national interest because he wanted to produce fine wines in a 750ml bottle, with the goal of exporting part of his production. By that time, the entire production was just for the local market, and neither bottle packaging nor quality wine was the rule.

Vineyards at Bodega Casa Grande

For a long time, when people used to talk about Uruguayan fine wine, they were mainly talking about wines made in the departments of Canelones and Montevideo, which accounts for 78% of the total planted area (66% and 12%, respectively). But things have changed. Even when the major production is still located in these areas, other regions are making excellent and recognized labels. As a side note, a high percentage of wineries are now part of Uruguay Sustainable Viticulture Program, a program committed to produce wines which come from traceable, environmentally friendly systems.

ATLANTIC WINES: Uruguay is located in the same parallels of some of the vineyard lands of Argentina, Chile, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand (30° to 35° of south latitude); however, for many reasons Uruguay tends to be comparable to European wine regions, particularly because it has a huge Atlantic influence on its wine regions.

As previously said, you can find vineyards almost everywhere in the country but the southern part, closest to the coast, is by far the most important zone in terms of fine wine production. Canelones and Montevideo take the lead, followed by Maldonado (where the famous Punta del Este is located), Colonia and San José.

Map via: https://uruguay.wine/es/regiones/

Uruguay is relatively flat, with some areas with gentle slopes, so altitude does not play a big role in terms of viticulture. What is more important is the proximity to the water, as Tim Atkin -Wine Writer and Master of Wine- explained when I asked him about the expression of the different Uruguayan wine regions. This is not only about the ocean, Uruguay has also a marked influence from the Río de la Plata, an estuary formed by the union of Paraná River and Uruguay River, and the vineyards closer to these rivers are warmer than those more to the east, with major influence of the Atlantic.

There are different types of soils, the majority generated from a sedimentary basin in Montevideo/Canelones. The area around Melilla (Montevideo) contains more clay, while Las Violetas (Canelones) is characterized by silt/clay sediments. Other areas in this department contain pink granite as well, like where Bodega H. Stagnary is located. The so called Oceánica/Atlántica region, where Maldonado is located, is the zone with the most Atlantic influence, higher altitude than the rest of the wine regions, and also a bigger geological diversity: crystalline rocks with some quartz incrustations, alluvial and gravel soils in the valley, and weathered granite. All of them have formed, throughout millennia, the ballast of the region, a soil full of minerals which gives rise to one of the greatest wines of Bodega Garzon: Balasto. To the west, in Carmelo, located in Colonia’s department, climate is influenced by the estuary of the Río de la Plata. Daniel Cis, oenologist of Bodega Campotinto and wine consultant of many wineries in the area, explains that “for our location, we typically are one or two degrees Celsius warmer than other wine regions and, as a result, it gives us around one week of ripeness ahead”. About the soils, he says, “in general the area has deep soils, with a low level of clay. Very permeable soils with good drainage, which is essential to prevent fungal attack”.

.

Uruguay is a four-season country, but not extremely marked. During summer, temperatures are mild to hot, and drop at night giving a considerable diurnal swing, which is great for the grapes; in winter, the weather is not excessively cold. Uruguay used to have an abundance of good quality water thanks to the proximity of numerous rivers; however, due to climate change, things are different today and, unlikely before, Uruguayans are now worried about drought. This is one of the challenges the industry is facing. Eduardo Felix from Inavi explains that vintages in Uruguay are not stable. Last year and this year were very atypical. “We had a 30% harvest loss, but quality has improved according to producers”, Felix said. This is related to the quote of Tim Atkin in his 2021 Uruguay Special Report, where he says that “climate change is, by and large, a boon for its wine industry”. I had the chance to ask Tim if he was still thinking the same way, and he said yes. “Maybe in summer slightly warmer regions are having problems with the absence of rain and the heat; but generally speaking, these early vintages have been a very good thing”. I also had the opportunity to visit in February/March Bodegas Carrau and Bodega Casa Grande. Marcos Carrau and Florencia de Maio coincide, saying that due to the dry season, the harvest was brought forward, giving as a result a very healthy bunches, grapes with lots of sugar, good acidity, and right phenolic ripeness. Less quantity, more quality.

Daniel Cis also commented that “the vines are responding very well, especially because Uruguay tended to have very high humidity levels and now it is all the way around. We are thinking of irrigating vineyards for new plantings and, for the older vineyards, have irrigation as an option to not compromise the grape quality, in case the drought continues.

.

In January, Leo Guerrero, Sommelier and Iberpark Brand Ambassador, prepared for me a sensational wine tasting. “I want you to taste different varieties, but also different zones from Uruguay”, he said. We had the chance to taste a delicate Rosato di Sangiovese from Bodega Sierra Oriental (Maldonado), a vibrant Albariño from Bodega Casa Grande (Canelones), a natural Barbera wine made by Pablo Fallabrino (Canelones), a lovely Tannat del Litoral from Bodega Campotinto (Carmelo), and a splendid and elegant Salto Chico Tannat Reserva Especial (Salto). It was a great opportunity to taste the expression of different Uruguayans regions: the minerality from Maldonado, which come from the soil but also from the ocean breezes (saltiness!); the roundness of the wines from Canelones (great balance!), the “stone minerality” and the intense nose from Carmelo (warmer zone, river influenced!), and the sweet ripeness from Salto (northern and warmer climate).

Having said that, it looks like today the Uruguayan wine industry is not only about Tannat…we are talking about a wine country that is capable of producing great wines, with an impressive diversity in terms of grape varieties, regions, and styles. A wine scene which is increasingly diverse, according to Tim Atkin, who also told me: “I think the potential is definitely huge, and what we are seeing now is just the beginning of a fine wine culture”.

THE WINE SCENE AND ITS ACTORS: The industry had experienced some important changes since 1990, when the Vineyard Conversion Pilot Program (Programa Piloto de Reconversión del Viñedo) began. The area planted with low quality vines was reduced and the different varieties of Vinifera grapes have been cultivated in areas where they show their best potential. The industry has been focused since then on making more fine wines than common wines. New oenologists, younger generations taking important roles in the family wine business, and old “new” grapes listed in many wineries’ portfolios are some of the latest changes in the industry. According to Daniel Cis, “we are now studying soils and climate, thinking what to plant and where to plant the vines. Precision viticulture, looking for which variety is going to give better results in which site.”

The author, Elizabeth Yabrudy with Marcos Carrau

I personally feel that Tannat-based wines have experienced a great evolution. I remember drinking -some twenty years ago- red wines from Uruguay that were very oaky, too powerful (and not in a positive way), full of immature tannins. But today, things are very different, although some people still think that the use of oak is still not well managed. For Tim Atkin “the local market is still a little too dependent on oak, and many people are making wines with oak to sell it in the local market, and that excess of oak is necessarily not something that people is looking for on export markets”. But it is important to mention that the way Uruguayan oenologists are utilizing oak is different now.

Daniel Cis agreed with Atkin. “To improve our winemaking, we have decreased the oak level, even if a part of the market asks for it. We have to keep looking for place and fruit expression, especially if we want something more than a wine from Uruguay, but a wine from a specific zone of Uruguay.”

According to Eduardo Felix, “we went from producing ´frenchified wines´ (15%to 16% abv., with overripe berries, hard and heavy wines, full of oak…) to produce more ´italianized wines´ (fresher and fruiter, micro-oxigenated, aged in botti grandi instead of regular barrels…)”. And that is basically the same message I received from Marcos Carrau, who commented “today we have a kinder and friendlier Tannat, with lower alcohol content, better balanced […]. We use French and American oak, and Tannat seems to like the last one very well”. Daniel Cis says: “we changed for good. Our Tannat is now drinkable, concentrated and expressive, but not rough”.

The great thing about Tannat, the icon red grape of Uruguay with 27% of vineyard acreage, if that it is a very versatile grape: you can get carbonic maceration wines (e.g. Pizzorno Mayúsculas Tannat Maceración Carbónica), passing through wines without or with just a bit of oak (e.g. Campotinto Tannat del Litoral, Cerro del Toro Tannat Línea Clásica or Familia Deicas Atlántico Sur), and to find wines with medium to long aging like Gran Tanaccito from Bodega Casa Grande or Bouza Tannat B28, among many others. Besides, there are beautiful rosés like Artesana Tannat Rosé, as well as some sparkling wines (e.g. Río de los Pájaros Brut Nature Tannat, from Bodegas Pisano), many blends (e.g. Artesana Tannat/Zinfandel, Juan Carrau Tannat/Cabernet Sauvignon, Bouza Monte Vide Eu from Tannat/Merlot/Tempranillo), and last but not less, the sweets Tannat liquors.

.

A great wine exercise is to taste a flight of Tannat with similar winemaking techniques, from different Uruguayans wine regions. If you do so, and you are not a Tannat lover yet, here is a comment from Florencia de Maio, the young oenologist of Bodega Casa Grande, that could inspire you: “usually people do not fall in love with Tannat at first sight. Tannat wine is shy… usually it does not say too much in the nose, but when you learn to know it, you know that the best will come when you feel all the flavors in your mouth”.

Uruguay’s wine regions have been compared many times with Bordeaux, France, mostly because of the maritime climate, even when Uruguay used to have more rainfall than Bordeaux (things have changed the last few years!). In any case, it is not a coincidence that some of the new grapes approved in Bordeaux (2021) have been cultivated in Uruguay for some years now, giving excellent results.

Talking about the whites, there is Albariño, that has become the spoiled girl. It is no longer a fashion grape, it has, as Tim Atkin mentioned, “a massive potential”. There is a fact that Tim also commented on, and it is that many wineries are planting it, producing good examples with this grape. “There is something about Albariño, particularly when the wines come from Maldonado, where you can get closer to the ocean, the ocean breezes, the volcanic soils on the slopes… Again, I think there is a lot of potential for Albariño and, for me, it is Uruguay´s best white grape”, affirmed Tim. Of course, when we talk about Maldonado, it is impossible not to think about Alto de la Ballena that was the first winery in the area (2001) and, of course, about Bodega Garzon, probably the biggest winery in Uruguay, main wine exporter, responsible in a great way for putting the name of Uruguay in the map as a wine country producing high quality wines.

The Winery at Bodegas Carrau

However, the history of the Albariño in Uruguay began with Bodegas Bouza. As Cristina Santoro—Exports & Marketing Manager—told me that the Bouza family is from Spanish origin, specifically Galician. “When they started the project and thought about the varieties they wanted to have, of course Albariño came right away […]. It was planted in 2000, and the first harvest was in 2004”.

The French Viognier has also registered an increase in both, vineyard area and production, of course, not as significant as Albariño. It is not very well known yet, and is not an easy grape to cultivate but its defenders told me that if you control the Viognier in the vineyard and recognize its versatility, it is so great. Viognier is becoming the white grape of Carmelo, and it is one of the favorite grapes of Daniel Cis.

When I asked Eduardo Felix -who by the way was responsible for the first Albariño´s harvest in Bouza and Garzón- about the future of the Uruguayan wine industry, he told me that “the issue of water deficit and climate change leads to wonder what viticulture we are going to aim for. The focus is on the following grapes in terms of the reds: we will stick with Tannat, but we will pay attention to Merlot, Marselan and Arinarnoa”, he said.

.

Marselan and Arinarnoa have registered a recent increase in Uruguay, not only in area, but also in production. Both red grapes are also now on the list of the varieties allowed to be in Bordeaux blends.

Uruguay has planted more than 185 hectares of Marselan (3% of the total of the total vineyard hectares). It is a French cross between Cabernet Sauvignon and Grenache, created by professor Paul Truel more than sixty years ago (1961). Marselan is very well adapted to Uruguay, where it has been planted for around 20 years. It is a variety highly resistant to fungi and other common diseases of the vines, which is perfect for the country climate. There are many wineries producing 100% Marselan in Uruguay. Some of them are Establecimiento Juanicó, Bodegas Carrau, Bertolini & Broglio, Dardanelli, and Chiapella, among others. You can find diverse styles, young/fresh to bold/intense, but generally purple in color, fruity aromas, with medium to high acidity, and medium tannins.

Talking about Arinarnoa, there are only about 63 hectares planted, which is around 1% of the total area planted with vines. However, this aromatic and fruity grape has conquered many winemakers in the country. It is also a French grape, a cross between Tannat and Cabernet Sauvignon, created in Bordeaux, in 1956, by the French Basque researcher Pierre Marcel Durquety from the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique. It found a home in Uruguay since 1980, and from there has been showing a significant growth, especially in the last twelve years (it grew from around 10 hectares in 2011 to more than 60 in 2021); it also behaves greatly in the vineyard when its production is controlled, and also is great in oenological terms. It matures late in the harvest season, usually after Tannat but before Cabernet Sauvignon.

I would say that one of the main promoters of the cultivation and growth of Arinarnoa is Florencia De Maio, who also happened to be the fourth generation of viticulturists and winemakers in her family. She says that Arinarnoa is the future of Uruguay. During my visit to Bodega Casa Grande, she told me “no one got much out of it for varietals, it was used for blends because it has a lot of aromas and a lot of color. We launched our first 100% Arinarnoa in 2013. We have been testing and changing the style, including passing it through oak, because we understood that it has potential to evolve”.

The author, Elizabeth Yabrudy in the vineyards at Bodegas Bouza

Bodegas Carrau also has a very expressive and elegant Arinarnoa. I had the chance to taste it with Marcos Carrau. The winery has around one hectare of Arinarnoa, planted in Las Violetas, Canelones, since 1996. However, the first varietal showed up in the market in 2018, as a part of the Colección de Barricas line.

Other producers of Arinarnoa are Giménez Méndez, Bresesti, Cantera Montes de Oca and Cerro Chapeu. Do you know what to expect? In case you have not tasted it yet, it has a deep red color, shows fruits and spices in the nose, has a great tannic structure and good acidity. Excellent when young, but also capable of interacting with oak without losing its varietal expression. The trend of Uruguayan winemakers is to apply second-use barrels or Hungarian oak to avoid overshadowing the fruity expression of the variety.

SURPRISE! MORE WINES TO TASTE: Now you know that Uruguay produces excellent Tannat, Marselan and Arinarnoa, and if you like white grapes, you have to try their Albariño and Viognier. But this is not all! If you come to Uruguay, make good friends because you will have to uncork so many bottles of wine.

In the red field, you must try their wonderful Merlot, but also buy some of their Pinot Noir, Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot and Nebbiolo wines. According to Tim Atkin, “Cabernet Franc has a good future, although I would look over some other varieties like Sauvignon Blanc which I think has a good potential”. So for whites, taste their Sauvignon Blanc and look for the few Petit Manseng they have, including the one from Bodegas Carrau.

If you like Spanish varieties, also check out the Tempranillo wines, especially Bouza! If you are an Italian grape lover -and also curious about Natural wine-, Pablo Fallabrino has a lot to offer: from Arneis to Nebbiolo, passing through Barbera and Dolcetto, and some other grapes. Bouza has an enchanting Riesling that is a must, Artesana is the only winery with a portfolio where Zinfandel is one of the main varieties, and Florencia from Bodegas Casa Grande is probably releasing this year another grape that make her eyes spark when she talks about it: Caladoc, another French grape, a cross between Garnacha and Malbec. If you like sparkling wines, they have excellent ones too!

Not in Uruguay? You will probably only find in the stores some Tannat, a few bottles of Albariño, and perhaps Merlot, Cabernet and Tannat-based blends. If you go to Brazil, you will have a better chance to get some Marselan or Arinarnoa, as well as other great bottles made in Uruguay.

But if you visit this beautiful country, do not hesitate to allocate part of your travel budget to buy Uruguayan wines and to visit some wineries in the different wine regions, taking Los Caminos del Vino and some other paths. The portfolio is huge, and wines and wineries are both worth it!

Elizabeth Yabrudy

I would like to thank to the following people who took the time to talk with me about the Uruguayan Wine Industry:

- Eduado Felix, Inavi’s Technical Advisor (January 19, 2023)

- Leo Guerrero, Sommelier and Iberpark Brand Ambassador (January 23, 2023)

- Cristina Santoro, Bodegas Bouza Exports & Marketing Manager (January 25, 2023)

- Marcos Carrau, Production Manager at Bodegas Carrau (February 10, 2023)

- Tim Atkin, Wine Writer and Master of Wine (February 13, 2023)

- Daniel Cis, Oenologist of Bodega Campotinto (February 20, 2023)

- Florencia de Maio, Oenologist of Bodega Casa Grande (Febrero 22, 2023)

References/For more information:

About the author: Elizabeth Yabrudy, CSS, CSW, CWE is a sommelier and journalist currently residing in Uruguay. To date, she is the only South American to have achieved the Certified Wine Educator designation from the Society of Wine Educators. In addition, Elizabeth is the winner of the 2018 Banfi Award, having received the highest combined total score of any candidate sitting the CWE in 2018. She stays busy teaching and writing about wine and spirits, as well as leading tastings and service training. In addition to her wine and spirits credentials, Elizabeth has a Master’s Degree in Electronic Publishing from City University in London. You can find her on Instagram: @eyabrudyi

Photo credits: Elizabeth Yabrudy

In a newsflash from France, AOC wines—in some cases, to a limited degree and with specific pre-approval—are now allowed to innovate (just a little).

In a newsflash from France, AOC wines—in some cases, to a limited degree and with specific pre-approval—are now allowed to innovate (just a little).