While math might not have been your favorite subject in school, you most likely find the need to use math at least sometimes, even in the study of wine!

Last week, Mark Rashap, CWE gave us some excellent explanations of some wine-related mathematical conversions as they pertain to area, volume, and weight. In this second installment of “The Numbers, in Perspective,” Mark will tell explain the mathematical calculation behind yields. Hold on, this won’t hurt a bit….

All about that yield: how much wine can that vineyard produce? Sometimes, it is all about yield. As every good wine student knows, yield is where we start getting into a factor of quality. There is some evidence that the lower the yield, the higher the quality, within a certain range—and that’s a great debate for another time and place. As for the math, pure and simple, in the United States, we most often refer to vineyard yield in terms of tons per acre. In Europe, it is most often expressed as hectoliters per hectare. As tons=weight and hectoliters=volume, it is not possible to come up with an exact conversion. However, we can find an equivalency to give us a way of comparing the two systems.

Consider this: Cornell teaches that 1 ton of grapes will yield 150 gallons of wine, or 5.67 hl. If we consider that is per acre and convert to hectares, we have our factor: 1 ton/acre = 14 hl/ha

Using this factor, we can have some fun comparing yields per region. I always think of 4 tons/acre as entry into the quality realm of wine. According to Robert Craig, this is the approximate yield of the valley floor AVAs of Napa. Using our conversion factor, we can calculate that 4 tons/acre = 56 hl/ha. Considering that 55 hl/ha is the maximum yield for Bordeaux AOC, and the maximum for Bordeaux Superior AOC is 50 hl/ha, we can see that the two areas have very similar yields.

In the mountainous vineyards of Napa, yield is closer to 2.5 tons/ acre, an equivalent of 35 hl/ha. On the extremes, I’ve seen yields as high as 10 tons/acre (140 hl/ha) in the Central Valleys of California and Chile, and yields as low as 5 hl/ha in the Priorat which equates to 1/3 of a ton per acre!

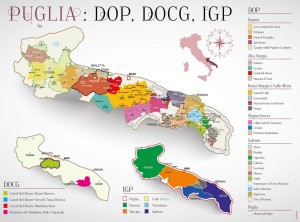

Here are a few more permitted yields, just for fun:

- Bourgogne AOC (white): 68 hl/ha

- Bourgogne AOC (red): 60 hl/ha

- Corton-Charlemagne (Burgundy Grand Cru) AOC (white): 58 hl/ha

- Montrachet (Burgundy Grand Cru) AOC (white): 48 hl/ha

- Corton (Burgundy Grand Cru) AOC (white): 48 hl/ha

- La Romanée (Burgundy Grand Cru) AOC (red): 38 hl/ha

- Corton (Burgundy Grand Cru) AOC (red): 35 hl/ha

- Alsace AOC (white): 80 hl/ha

- Alsace AOC (red): 60 hl/ha

- Sommerberg (Alsace Grand Cru) AOC (white): 55 hl/ha

- Beaujolais AOC (red) 60 hl/ha

- Morgon (Beaujolais Cru) AOC (red) 56 hl/ha

Sometimes, it truly is…all about that yield!

Post authored by Mark Rashap, CWE. Mark has, over the past ten years, been in the wine world in a number of capacities including studying wine management in Buenos Aires, being an assistant winemaker at Nota Bene Cellars in Washington State, founding his own wine brokerage, and working for Texas-based retail giant Spec’s as an educator for the staff and public.

Post authored by Mark Rashap, CWE. Mark has, over the past ten years, been in the wine world in a number of capacities including studying wine management in Buenos Aires, being an assistant winemaker at Nota Bene Cellars in Washington State, founding his own wine brokerage, and working for Texas-based retail giant Spec’s as an educator for the staff and public.

In August of 2015, Mark joined the team of the Society of Wine Educators as Marketing Coordinator to foster wine education across the country.

Are you interested in being a guest blogger or a guest SWEbinar presenter for SWE? Click here for more information!