Its a familiar story to wine enthusiasts…in 1855, Napoleon III, the Emperor of France, decided that France would host an event to rival the Great Exhibition held in London four years earlier. That event, the Exposition Universelle de Paris, would showcase all the glory that was France – including its finest wines.

Its a familiar story to wine enthusiasts…in 1855, Napoleon III, the Emperor of France, decided that France would host an event to rival the Great Exhibition held in London four years earlier. That event, the Exposition Universelle de Paris, would showcase all the glory that was France – including its finest wines.

One of the exhibitors was the Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce, which decided to feature a list of the region’s best wines. However, knowing better than to draw up the list themselves, they asked the Syndicat of Courtiers (Bordeaux’s Union of Wine Brokers) to draw one up.

It did not take the Syndicat long to think through the list; two weeks later, they were finished. Their original list included 58 of the finest Châteaux of the Gironde department – four first growths, 12 seconds, 14 thirds, 11 fourths, and 17 fifths. Apparently, the brokers did what brokers do: they assigned the rankings based on price, reasoning that the market, in its infinite wisdom, had already ranked the wines based on who was commanding the highest price. This move makes more sense if you know that in the 1850’s; the wine trade in Bordeaux was still largely controlled by the British.

The Syndicat’s original list ranked the Châteaux by quality within each class. Mouton-Rothschild, quite famously, was at the head of the seconds. However, the controversy concerning the entire list was such that by the time the Exposition rolled around, a few months after the list was first released, they had rescinded the quality listing within the categories, quickly claimed that no such hierarchy had ever been intended, and took to listing the Châteaux alphabetically.

The Syndicat’s original list ranked the Châteaux by quality within each class. Mouton-Rothschild, quite famously, was at the head of the seconds. However, the controversy concerning the entire list was such that by the time the Exposition rolled around, a few months after the list was first released, they had rescinded the quality listing within the categories, quickly claimed that no such hierarchy had ever been intended, and took to listing the Châteaux alphabetically.

As every good wine student knows, the only formal revision to the original list came in 1973, when, following a half-century of unceasing effort by Baron Philippe de Rothschild, Mouton was elevated from second-growth to first growth, and the winery’s motto became “Premier je suis, Second je fus, Mouton ne change.” (“First, I am. Second, I used to be. Mouton does not change.”)

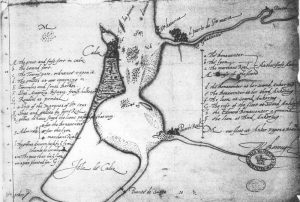

![9.8-The-Haut-Medoc-4-color-[Converted]](http://winewitandwisdomswe.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/9.8-The-Haut-Medoc-4-color-Converted-231x300.jpg) Since 1855, many changes have occurred in the names and ownership of the properties. However, as long as an estate can trace its lineage to an estate in the original classification, it can retain is cru classé status. Due to divisions of the estates, the 58 original estates now number 61.

Since 1855, many changes have occurred in the names and ownership of the properties. However, as long as an estate can trace its lineage to an estate in the original classification, it can retain is cru classé status. Due to divisions of the estates, the 58 original estates now number 61.

And now for the rest of the story…

As any good CSW Student knows, Bill Lembeck, CWE, has designed the maps for the last few editions of the CSW Study Guide.

Next month, (Spoiler Alert) SWE will launch its 2014 version of the CSW Study Guide, and Bill has once again designed and updated the maps for us – this time in color! As a special bonus, Bill has created this map of the Häut-Médoc which gorgeously lists the Châteaux of the 1855 Classification. A larger image and pdf of the map is available here.

Enjoy, and many thanks to Bill!