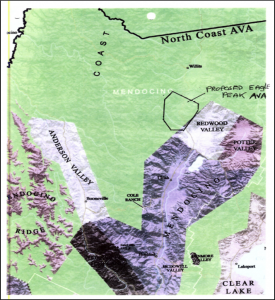

Map of the proposed (now approved) Eagle Peak Mendocino County AVA, from the TTB’s original docket (see link below)

Not even one day old….today – October 9, 2014 – the Federal Register published a new rule establishing the 21,000 acre Eagle Peak Mendocino County AVA.

This new AVA, which will become “official” one month from today, is located entirely within the North Coast AVA – it is not, however, located within the Mendocino AVA, nor is it a subregion of the Mendocino AVA.

The Eagle Peak Mendocino County AVA is located adjacent to, and to the west of the eastern “wing” of the Mendocino AVA. As a matter of fact, the Mendocino AVA and one of its subregions, the Redwood Valley AVA, both had their boundaries moved. Each had its acreage reduced by about 1,500 acres. This was to eliminate any overlaps, and because the TTB was convinced that the area in question has more in common, terroir-wise (and especially climate-wise) with the newly-approved area than it has with its former parents.

Here are a few more things you might want to know about the Eagle Peak Mendocino County AVA:

- The name of the AVA was approved as “Eagle Peak Mendocino County” as opposed to just “Eagle Peak” for good reason: while a 2,700-foot high mountain known as “Eagle Peak” is indeed a major feature of the region, there just so happen to be 47 other mountains in the US that are named “Eagle Peak.”

Another reason the long version of the name was required for approval is that there was some concern that an AVA named “Eagle Peak” might confuse consumers, and/or might infringe upon the “Eagle Peak Merlot” brand produced by Fetzer Vineyards.

Another reason the long version of the name was required for approval is that there was some concern that an AVA named “Eagle Peak” might confuse consumers, and/or might infringe upon the “Eagle Peak Merlot” brand produced by Fetzer Vineyards.- The new AVA is located 125 miles north of San Francisco. The nearest city in this mountainous region is Ukiah; the AVA is situated about 10 miles north and slightly to the west of Ukiah.

- There are currently at least five commercial vineyards operating in the area, with a total of just over 115 acres of vines.

- The region’s many streams feed into the headwaters of the Russian River, which flows through Mendocino and Sonoma Counties on its journey to the Pacific Ocean.

- Soils are shallow and composed of mainly sandstone and shale.

- The typical climate conditions of the area include: marine fog and breezes, cool temperatures in the spring, warm-to-hot summers and gusty winds.

For more information, including all of the details on the Federal docket, click here.

For a shortcut to the map submitted with the application, click here.

Post authored by Jane A. Nickles, CSS, CWE – your SWE Blog Administrator

Click here to return to the SWE Homepage.

![9.8-The-Haut-Medoc-4-color-[Converted]](http://winewitandwisdomswe.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/9.8-The-Haut-Medoc-4-color-Converted-231x300.jpg)