…..

Today we have a guest blog from Lucia Volk, CSW, reporting from Germany, where she is visiting the lesser known wine regions.

If you are a fan of Riesling, you undoubtedly know the Rheingau. The Rheingau is home to Germany’s prestigious, over 1,000-year-old Schloß Johannisberg, where late harvest (Spätlese) was allegedly invented. You probably also know the neighboring Rheinhessen, Germany’s largest and most productive wine area.

Next to those Riesling wine super-powers, the Mittelrhein region, which the German Wine Institute ranks second-to-last by size – only Hessische Bergstrasse is smaller – has to struggle to be noticed. It does not help that regional wine advertisement budgets in Germany are pegged to acres cultivated, or that the Mittelrhein extends into the jurisdiction of two German states, Rhineland Palatinate and North Rhine Westphalia, that do not always agree politically. Depending on the size of the harvest, the Mittlerhein region contributes somewhere between 0.3 and 0.5% to Germany’s wine total. Let’s face it: even within Germany, Mittelrhein Riesling is an insider wine.

Castle Reichenstein

Most of this lesser-known region – almost 85% – consists of terraced slate slopes that require manual labor, and yields are low. Because of the extra labor hours required per acre cultivated, it can be difficult to find a successor for a Mittelrhein winery after a vintner retires. The overall area under wine has fallen from 1,800 acres in the early 1970s to approximately 1,100 now.

Fortunately for wine lovers, the numbers are beginning to hold steady. About 70% of grapes planted are Riesling, another 10% go to Müller-Thurgau and Kerner combined, 10% to Pinot Noir, and the remaining 10% to Pinot Gris, Pinot Blanc, Dornfelder, Portugieser and others. In other words, the Mittelrhein is primarily a place for white wine lovers, although Pinot Noir acreage is on the rise.

Historically, the Rhine river separated the Roman Empire from the realm of the Gauls. The Romans planted the first vines in the region, and they built the first fortifications, a tradition that was adopted by German nobility in the Middle Ages. Fortresses, castles and and customs towers – the Rhine river was an important trading route – line the hilltops. These historical remains – many carefully restored, others in ruins – create the backdrop for the “Romantic Rhine.“ Tourists can book river boat trips, with scheduled stops for guided castle tours and subsequent wine tastings. Because of its cultural and historical significance, the Mittelrhein valley was designated a UNESCO world heritage site in 2002 , thirteen years before Champagne and Burgundy received similar badges of distinction.

The Rhine River is responsible for the favorable growing conditions in most of Germany’s northern latitude vineyards. Already at its source, close to Lake Constance, grapes are under cultivation, and if you follow the stream you will be able to taste, in succession, Baden, Pfalz, Rheinhessen, and Rheingau wines, before you reach the wine growing limit (for now) at the Mittelrhein. Mild winters allow for early buds in spring and extended sunshine permits ripening into October, resulting in unique aromas that are difficult to replicate in Riesling vineyards elsewhere.

Bopparder Hamm, part of the Mittelrhein’s Loreley Bereich (photo by Lucia Volk)

The picturesque Mittelrhein geography was created at the end of the Devonian Age – 360 million years ago – when what used to be the bottom of the prehistoric ocean rose up all at once, and the water subsequently had to cut a path through the rocks. The Anbaugebiet Mittelrhein is divided into two districts (Bereiche): the larger Loreley** between Bingen and Koblenz in Rhineland Palatinate, characterized by slate and greywacke soils, and the smaller Siebengebirge between Neuwied and Bonn in North Rhine Westphalia, which also contains volcanic rock and loess.

Eleven larger sites (Großlagen) are divided up into 111 vineyard sites (Einzellagen). The soil is nutrient-poor and well-drained, so roots go deep. With the exception of irrigating freshly planted vines, most Mittelrhein winemakers dry-farm, although irregular rainfall over the last decade has some winemakers worry about the increasing stress levels of their vines. A quarter of the harvest turns to Prädikatswein, and the rest to Qualitätswein. Deutscher Wein or Landwein production is negligible.

You can still find cooperatives that produce Mittelrhein wines, a tradition that dates back to the late 1800s, when phylloxera devastated most of the region’s vineyards. But more commonly, you now find small family wineries that trace grape production back for several generation, as well as new ventures of enterprising young winemakers.

Photo Credit: Lucia Volk

For instance, Peter Jost and his daughter Cecilia today run the Toni Jost winery, named after Cecilia’s grandfather. Their prized Einzellage is the Bacharacher Hahn, which overlooks the Rhine outside the town of Bacharach. The word Hahn translates to rooster, which decorates the Jost label, but the vineyard’s name probably stems from Hain (=grove). Founding members of the VDP – Verein Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter – their estate comprises 40 acres, not all of them on the Mittelrhein, and they produce almost 100,000 bottles a year, predominantly Riesling.

Following VDP regulations, their vineyard sites are ranked according to their potential for excellent, terroir-specific wine. Additionally, Cecilia recently introduced Devon-S (S for Schiefer=slate) Riesling that brings white flowers to the nose, offers stone fruit in the glass, and finishes with pronounced Mittelrhein minerality. If you do not know what rock tastes like, Devon-S will take you there.

In the middle of the Mittelrhein, Florian Weingart makes his wines in premium Einzellagen between Boppard and Spay, especially Engelstein and Ohlenberg. Dedicated to the local soil, he searched historical records for documentation of former vineyard sites – areas that had gone wild – and spared no effort to rehabilitate the most promising among them.

Florian Weingart on camera for Terry Theise’s Leading between the Vines documentary (photo by Lucia Volk)

On 11 acres, he produces around 45,000 bottles of wine in a regular year. In 2014, when late rains and pests ruined much of the Riesling crop, it was closer to 30,000. He coaxes each of his wines to develop his own character, using ambient yeast, if possible, and he allows them to finish fermenting early, if that is what the yeast decides to do. If his wine cannot obtain a certain (legal) quality level, because of it, he will rename (and effectively declassify) it. A philosopher in his spare time, he has started writing a Modern Ethics of Wine based on his “less is more“ winemaking principles.

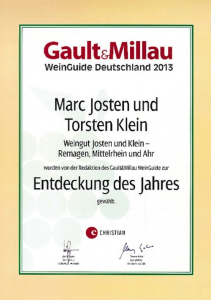

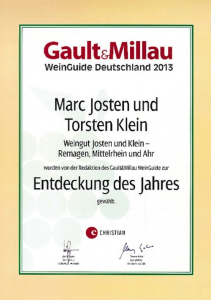

The town of Leutesdorf in the Siebengebirge Bereich of the Mittelrhein claims to be the last big bastion at the northern Riesling frontier. Here, wine technician Marc Josten and enologist Torsten Klein acquired vineyards in the famed Einzellage Gartenlay, where they produce both Riesling, and, in a bold move, Sauvignon Blanc. Their first wines were introduced in 2012, when they were still a garage winery in Remagen, operating out of rented space.

For their Sauvignon Blanc and some of their Riesling, they employ traditional, large oak barrels. While Riesling, Pinot Gris, and Sauvignon Blanc comprise 75% of their total production, they also grow 25% Pinot Noir in vineyards in the neighboring Ahr region, a red-wine stronghold. Altogether, they work about 14 acres. They focus exclusively on dry wines, and promote food pairing events jointly with local restaurateurs. Josten & Klein were the prestigious Gault&Millau Wineguide’s 2013 Discovery of the Year.

For their Sauvignon Blanc and some of their Riesling, they employ traditional, large oak barrels. While Riesling, Pinot Gris, and Sauvignon Blanc comprise 75% of their total production, they also grow 25% Pinot Noir in vineyards in the neighboring Ahr region, a red-wine stronghold. Altogether, they work about 14 acres. They focus exclusively on dry wines, and promote food pairing events jointly with local restaurateurs. Josten & Klein were the prestigious Gault&Millau Wineguide’s 2013 Discovery of the Year.

A relatively recent initiative specific to the region is the Mittelrhein-Riesling Charta. Participating winemakers agreed on a unified front label for their bottles, which shows the Charta grape symbol, the names of one of the categories – Handstreich, Felsenspiel and Meisterstück – and the two words: Mittelrhein and Riesling. Winery-specific information can be found on the back label. If the categories remind you of an Austrian classification system, you are correct. The Mittelrhein group consulted with Wachau wine producers who use similar designations and production guidelines for a variety of their wines.

…

Rather than focus on terroir (i.e. Bacharacher Hahn) or ripeness category (i.e. Kabinett or Spätlese), the Mittelrhein-Riesling Charta promotes flavor profiles: light, easy-to-drink, food-friendly (= Handstreich, metaphor for “spontaneous, quick action”); medium, balanced, expressive, good on its own or with a meal (=Felsenspiel, “rock play”); or full-bodied, quite dry, deeply aromatic and lingering (=Meisterstück, “master piece”). With this approach, the Charta members avoid the traditional sweet, medium-dry, or dry labels that suggest sugar (and alcohol) levels matter most in wine. Think of the Charta as a new generation of Mittelrhein winemakers jointly re-thinking and re-branding what they think is important about a segment of their Riesling production. All of them continue to offer traditionally labeled bottles.

Next to well-known German Riesling exporters Leitz, Dönhoff, Dr. Loosen, Deinhard/Von Winning, or Schloss Johannisberg, winemakers along the UNESCO world heritage valley have an undeniable underdog status. You will not find Mittelrhein wine in many stores in the United States, but what wine drinker does not like the occasional treasure hunt for a rare bottle? For an authentic Mittelrhein Riesling experience, book a boat trip down the Romantic Rhine, open a bottle on the sun deck, and count the castles as you go by.

**The name for the Bereich Loreley derives from a famous promontory on the Rhine river near St. Goarshausen. Because of the narrow fairway, accidents were not infrequent before modern navigation technology. Poet Heinrich Heine turned the site of captains’ misfortune into a metaphor for unrequited love: the beautiful, blond Loreley perched on her rock, singing her siren’s song, while forever staying out of reach, caused men to lose their bearings, if not their lives. In English, it sounds like this.

Lucia Volk, CSW, is working on a manuscript on the lesser known wine regions of Germany. This summer, she discovered vineyards in Berlin, excellent Pinot Noirs along the Elbe and the Ahr, and phenomenal Riesling wines on the Mittelrhein. Her first SWE blog described the re-emerging wine region of Saxony.

Are you interested in being a guest blogger or a guest SWEbinar presenter for SWE? Click here for more information!

A guest post by Harriet Lembeck, CWE, CSE…

A guest post by Harriet Lembeck, CWE, CSE… At least 90% of Prosecco comes from the larger DOC area, which contains 556 municipalities. While most of Prosecco is produced in the plains, there is a lot of overlap. Many wineries produce under more than one designation, crossing regional boundaries.

At least 90% of Prosecco comes from the larger DOC area, which contains 556 municipalities. While most of Prosecco is produced in the plains, there is a lot of overlap. Many wineries produce under more than one designation, crossing regional boundaries.  Adami’s “Col Credas” Brut, from Dalla Terra Imports, was the driest and had a very fine bead.

Adami’s “Col Credas” Brut, from Dalla Terra Imports, was the driest and had a very fine bead.