Today we have a guest post from Jordan Cowe, CWE. Jordan gives us a little background on his upcoming Conference session on Wine’s Eco-Evangelists!

Wine’s Eco-Evangelists have a problem, a big one: For every person who supports what they do, there’s at least 2 or 3 more that are skeptics.

When I was first diving into the world of Eco-Friendly viticulture I held a fairly skeptical – if not cynical -view of the whole area. If I were to distill my thoughts from that time on the field down to what I thought of it, I would have defined my experiences with the three main areas of eco-wine as follows:

- Sustainability: A marketing buzzword used by nearly every winery in existence with little to no meaning left.

- Organics: A mix match of regulations aiming to achieve some unknown goal by making wines that were often fairly unimpressive.

- Biodynamics: A new age cult. Period. Seriously what’s up with these guys?

The reality is these are unfair assessments, but they are commonly held views on the subjects. Over time I have had chance to work for and speak with producers using these approaches and have realized that there’s a lot more happening here than it seems. What is really happening is a communication problem, people just don’t believe what they’re being told. Whether it’s overuse in marketing, disbelief in the actual benefits or simply getting a giggle out of the more mystical aspects, each area of eco-wine has to fight to overcome skeptics, even among fans of the wines and sometimes staff.

Sustainability truly has become a marketing buzzword, making it hard to distinguish who is truly embracing sustainability and who is just using it to help their brand. The biggest questions here become: If it’s good for the environment and quality does it really matter why they’re doing it? What exactly are they doing, do they detail their practices? At this point you can make a judgement for yourself, or taking it a step further several regional associations have developed their own sustainability certification to help ensure the word really means something.

For organics the idea is well meaning, reduce the use of synthetic chemicals in favor of more natural compounds. Part of the problem here has been the mix of certifications and awkward terms used across the field. Over time there has been increased standardization of practices, advances in understanding of the effects of organic compounds themselves and in general an improvement in the quality of the wines being produced. Like any field it can take time to figure out how to do it right and with maturity will come great strides. In the meantime how do you approach the fears about viability or even functionality and communicate the benefits.

At the far end of the eco spectrum is biodynamics, and a beast of a topic it is. I will be quite frank and say at the core of its ideology it does contain a fair amount of mysticism but the mystical aspects are relatively unrequired for certification. The ultimate goal with biodynamics today is to bring balance to the farm and related ecosystems. Some producers fully embrace the mystical side of biodynamics, but the more you get to know producers it would seem many have simply the accepted system itself with the knowledge that it does appear to produce a healthier farm and better wines, they aren’t worried about why. Some of the largest producers are in fact actively trying to pin down a scientific basis for the practices realizing that the mystical explanations can hurt the movement.

The focus with all three of these ideologies is to create better wines while having a positive impact on the environment. This is ultimately a noble goal, and one that is often achieved, with many of the world’s top vineyards meeting the criteria for one of these categories whether they publicize it or not. Many of their communication problems come down to their existence as ideologies, proponents view the topics as often very black and white, all or nothing proposals. This makes finding a common ground with which to explain their ideas to outsiders difficult. Combine this with some aspects that are relatively unexplainable and you have a problem on your hands.

Through my interactions with producers I’ve increasingly realized this communication gap is a big problem and have set out to examine the topics in depth to find out for myself what they are really all about. As an outside observer I’ve examined the good and the bad in these topics, I’ve looked at the scientific basis behind some of the more esoteric practices and I’ve set out to find a way of conveying the basis of these ideas while avoiding the easy mystical or just because answers. Through a better understanding of these ideals I hope to enable more wine lovers to be eco-evangelists, to appreciate the hard work and experimentation that goes into making outstanding wines in an environmentally conscious manner.

At the heart of it how can anyone be opposed to producers wanting to make better, more exciting wines all the while helping the environment? But do they actually have a positive impact on the environment? Are the ideas practical or is it just witchcraft and anecdotal evidence? How do you decipher all of the conflicting ideas and information out there?

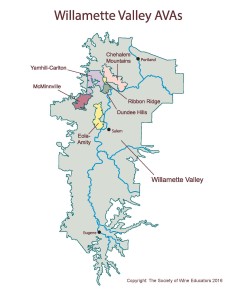

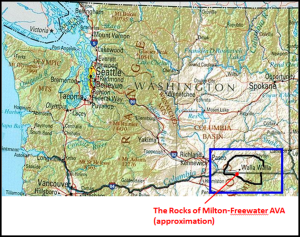

Join me at this year’s annual conference in New Orleans for my session “Wine’s Eco-Evangelists: Saving the world one glass at a time, ” where I will aim to remove the fog covering eco-friendly viticulture and winemaking philosophies and explain what each of these areas of the wine world actually entail. We will taste through some key producers from exciting regions in the world of eco-viticulture and judge for ourselves if the wines live up to the hype that they earn.

Jordan Cowe is a Certified Wine Educator and Sommelier from Niagara Falls, Canada. As an independent educator Jordan focuses primarily on educating wine professionals and developing a friendly, open minded approach to wine service and sales. Eco-wines are just one of the many interests Jordan has within the world of wine, his focus strongly directed toward the unusual and esoteric topics. Jordan’s other works and previous presentations can be found on his website at http://www.oenosity.com.