Today we have a guest blog from Certified Wine Educator, Brenda Audino. Brenda shares with us a topic that is dear to the hearts of wine lovers the world over….books about wine!

Today we have a guest blog from Certified Wine Educator, Brenda Audino. Brenda shares with us a topic that is dear to the hearts of wine lovers the world over….books about wine!

In the pursuit of greater wine knowledge I have found the greatest expense to be in the wine. It takes a lot of wine bottles to truly “understand” the nuances of each wine region both great and small. The second largest expense for me have been the wine books. There are an endless amount of books covering everything from encyclopedic to specifics; from terroir to marketing. I have found though that even with an extensive wine library there are a handful of books that are my “go to” selection in starting any wine related research.

I have categorized my wine library into three main categories; general reference, specific area (viticulture, vinification, and wine region) and wine themed pleasure books. This categorization enables me to quickly gather the books I need.

Of course, the list of my favorite wine books includes the CSW Study Guide – but I assume that is that same for all of you as well!

So, here are a few of my favorite books and why they are always next to me at my desk:

The Oxford Companion to Wine – 3rd Edition, Jancis Robinson: This is definitely encyclopedic and not one I would recommend to read from cover to cover. Excellent resource in digging deeper into a subject. Fair warning though, in each entry there will be reference to other sections and these refer to even more sections that can keep you flipping pages for hours.

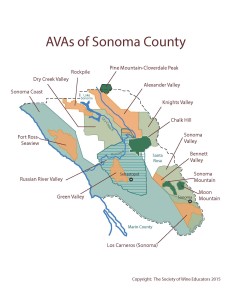

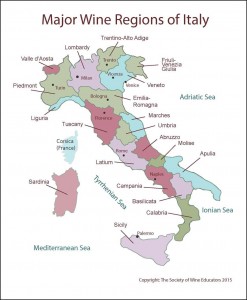

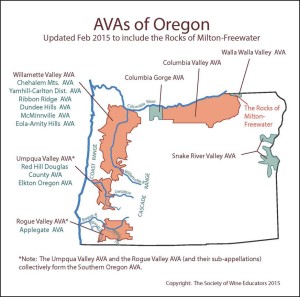

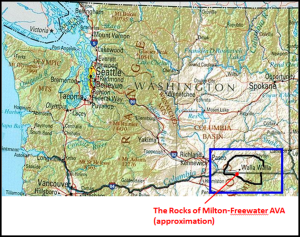

The World Atlas of Wine – 7th Edition, Hugh Johnson & Jancis Robinson: This book is quite large, but not overly daunting to read through a chapter or two a week. The info graphs are clear and assist in the understanding of the corresponding text. While there is beautiful photography throughout, my favorite part of this book must be the maps! They have a high level of detail, but are also easy to review.

How to Pronounce French, German, and Italian Wine Names; Diana Bellucci: Although I dislike butchering foreign wine names in the privacy of my own brain, when it comes to speaking them out loud it is extremely important to get the pronunciation correct. As a wine educator it is critical! I have quickly come to realize that my two years of French in high school did little to prepare me in my wine career. This book with its easy to understand techniques helps me get as close to the true pronunciation without having to be fluent in all of these languages.

How to Pronounce French, German, and Italian Wine Names; Diana Bellucci: Although I dislike butchering foreign wine names in the privacy of my own brain, when it comes to speaking them out loud it is extremely important to get the pronunciation correct. As a wine educator it is critical! I have quickly come to realize that my two years of French in high school did little to prepare me in my wine career. This book with its easy to understand techniques helps me get as close to the true pronunciation without having to be fluent in all of these languages.

Understanding Wine Technology; David Bird, MW: I am not a winemaker and even though I have visited many wineries nothing can be said for the hands-on experience working day in day out guiding a wine from vine to bottle. This book, though, for me, gives the information needed to gain a glimpse into the science behind the wine. This book covers a broad range from the mysteries of the vineyard, the components of grapes, producing and adjusting the juice (must), complexities of fermentation and the winemaking process, quality control and assurance.

Wine Grapes, Jances Robinson, Julia Harding, & José Vouillamoz: This is my newest “wine geek” book. Detailed origins, viticultural characteristics, where it’s grown and what its wine taste like on every grape imaginable along with many more that I never heard of. This is a tomb of a book, but completely satisfying to heave out for research on individual grapes. Jancis Robinson has released several pocket guides on wine varieties and this book feels like the culmination of all of these works with details of over 1300 different varieties. The Pinot pedigree diagram is more complete than my own family tree! The pictures of grape varieties look like pieces of frame-worthy art. This is a book I can (and do) get lost in.

Wine & War, Don & Petie Kladstrup: The story of how wine played a role in France’s fight during World War II. The narrative follows five winemaking families from France’s key wine-producing regions of Burgundy, Alsace, Loire Valley, Bordeaux, and Champagne and their struggles to save the heart and soul of France. I found this an enjoyable and lively read after a day of studying.

I now realize that I can and will have a lifelong mission to study and learn more about wine. I am also interested in what others find useful in their pursuit of knowledge. What are some of your favorite “go to” books that you use in your education journey?

I now realize that I can and will have a lifelong mission to study and learn more about wine. I am also interested in what others find useful in their pursuit of knowledge. What are some of your favorite “go to” books that you use in your education journey?

Post authored by Brenda Audino, CWE. After a long career as a wine buyer with Twin Liquors in Austin, Texas, Brenda has recently moved to Napa, California (lucky!) where she runs the Spirited Grape wine consultancy business. Brenda is a long-time member of SWE and has attended many conferences – be sure to say “hi” at this year’s conference in NOLA!

Are you interested in being a guest blogger or a guest SWEbinar presenter for SWE? Click here for more information!