Saint Amour claims to be the most romantic of the Beaujolais Crus. It’s tough to argue with the “romance angle” when a wine’s name translates – literally- to “Saint Love” and loosely to “holy love,” “pure love,” or a variety of other equally delicious and romantic terms. Duboeuf describes their Saint Amour as “the wine of poets and lovers.”

Saint Amour claims to be the most romantic of the Beaujolais Crus. It’s tough to argue with the “romance angle” when a wine’s name translates – literally- to “Saint Love” and loosely to “holy love,” “pure love,” or a variety of other equally delicious and romantic terms. Duboeuf describes their Saint Amour as “the wine of poets and lovers.”

According to the “Discover Beaujolais” website, more than 25% of the wine’s sales occur in February, around Valentine’s Day – most likely helped by the Smiling Cupids or hearts that adorn many of the labels. Suffice it to say that, with both the cheery name and the reasonable price (about one-quarter of the cost of Pink Champagne) going for it, this wine is ready for romance.

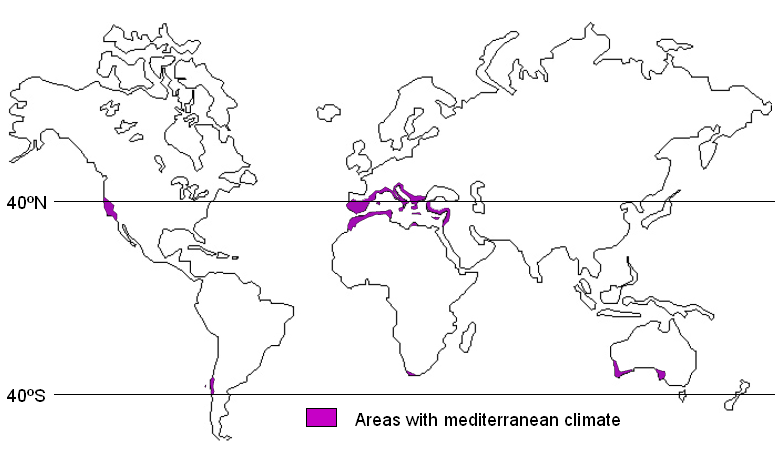

Saint Amour is the northernmost Cru of the region, located where the granite soils of Beaujolais – so prized for the growing of Gamay – give way to the limestone soils of the Mâconnais to the north, better suited for the cultivation of Chardonnay. Saint Amour actually borders the Saint-Véran AOC in the Mâcon, and many vignerons in the region own land and produce wine in both regions.

Not to quell the rumors of romance, but local lore actually suggests that the region was named after a Roman soldier rather than an angel of love. St. Amateur, the story goes, was a soldier of war who converted to Christianity after narrowly escaping death, and established a monastery overlooking the Saône River.

Not to quell the rumors of romance, but local lore actually suggests that the region was named after a Roman soldier rather than an angel of love. St. Amateur, the story goes, was a soldier of war who converted to Christianity after narrowly escaping death, and established a monastery overlooking the Saône River.

The wines of Saint Amour can be enjoyed while young, and while youthful often show aromas and flavors of cherry, berry, peach, apricot and spice. Most producers say the wines need at least a year to open up, and are at their supple best with two or three years of aging, when floral aromas start to shine. Some producers claim their Saint Amour is capable of producing vin de garde, wines suitable for aging, and can reveal their complex side anytime between four and 8 years after bottling.

Designated as a Cru in 1946, perhaps the wines of Saint Amour can remind us that love is grand in all its forms – through youth, middle age, and maturity – and that a good wine is always an excellent accompaniment to romance!

Discover Beaujolais: http://www.discoverbeaujolais.com/

Duboeuf/Saint Amour: http://www.duboeuf.com/en/page/Selection/Beaujolais-Fleurs-Saint-Amour#/en/page/Selection/Beaujolais-Fleurs-Saint-Amour