.

Today we have a guest post from SWE member Jan Crocker. Jan has just completed our CSW Online Prep Class and is planning on taking her CSW exam next month. Wish her luck!

Jan works on the “front line” of the wine industry as a beverage steward in an upscale grocer in Southern California. Read on as Jan shares about her recent trip to the Ramona Valley AVA.

Whenever I discuss California wine with wine shoppers at work, nearly all mention Temecula, since it’s extremely familiar to oenophiles in Orange County, California. I can also count on several folks each day singing the praises of the Napa Valley (“isn’t that where the greatest wines in the world come from?” they invariably comment), as well as Paso Robles and Sonoma.

However, because I relish exploring obscure wine varieties and regions—that’s why I’ve been a wine nerd for more than 15 years, after all—I’m genuinely excited about watching the emergence of a certain young American Viticultural Area that’s fast gaining acclaim among local wine writers, professionals and judges.

.

With that, I’ll present the 162nd AVA in the United States: the Ramona Valley AVA.

As the third AVA in the sizable South Coast “super AVA” at 33.1 degrees north, the Ramona Valley celebrated its 10th anniversary in January 2016. The region itself is 14.5 miles long and nine and a half miles wide, and is home to 25 bonded wineries within its 89,000 acres over 139 square miles. (Note to wine nerds everywhere: the other two AVAs located within the South Coast AVA are the San Pascual Valley, founded in 1981, and the Temecula Valley, founded in 1986.)

Located about 35 miles northeast of San Diego in north-central San Diego County, the Ramona Valley is a destination famed for its balmy climate throughout the year. On the other hand, the area is no stranger to scorching summers, with daytime temperatures often above the century mark. Winters, by contrast, are brisk, with afternoons reaching the mid-60s and nights often dipping below freezing. Small wonder: Ramona is exactly 25 miles east of the Pacific Ocean, and 25 miles west of the Colorado Desert. Rainfall is moderate, with roughly 16 inches each year.

Julian, the historic burg famed for its apple pies and winters with light snow, is a mere 22 miles east of Ramona and more than 4,200 feet above sea level. (That’s why I describe the Ramona Valley’s climate as “Mediterranean, with an asterisk.”)

.

Grapes thrive as a result of the Ramona Valley’s vineyard elevation: about 1,400 feet above sea level. At least two of the region’s wineries sit at nearly 2,000 feet at elevation.

Indeed, the Ramona Valley’s neighboring mountains, hills, and rocks are a force in defining the character of the region’s wines. The Cuyamaca Mountains, Mount Palomar, and Vulcan Mountain are the “high points” of the steep inclines surrounding the valley. At the western portion of the region, 2,800’ Mount Woodson does its part as a rain shadow by keeping the Pacific Ocean’s trademark fog and chill at bay.

Let’s get back to those rocks.

During each of the four visits my husband and I have made to Ramona, we’ve never failed to be wowed by the huge boulders and striking rock formations along picturesque Highway 67, the only path leading into the region. On our first trip in early 2015, I hummed “The Flintstones” theme as we approached those monster rocks, since many of them resemble Bedrock, the cartoon’s setting. The closeness of those boulders, however, kept us alert: We fervently hoped that we’d be spared one of our home state’s signature earthquakes during our drive.

.

Granite dominates the geological landscape, either in its original form as rocks or boulders or within the region’s loamy soil as decomposed granite. (During our four days in the region this August, we also spotted milky and rose quartz, as well as some tiny flakes of pyrite, during our “personal tours” of the 11 vineyards we visited.)

Granite’s presence also makes itself known in Ramona Valley wines: Of the 100 or so wines from the region that my husband and I have tasted in the last year and a half, all have an elegant flintiness and a backbone of minerality that’s riveting.

Southern California’s “soft chaparral” is the garrigue that shows up in Ramona Valley’s wines, reds especially. Many of my tasting notes include “sage and rosemary,” so it’s no mystery to find that flora in the region’s natural landscape, along with wild oak, toyon, chamise and numerous species of cacti.

Local winemakers embrace the Ramona Valley’s terroir, planting varieties that develop deep flavors as they echo the area’s climate, soil types and ever-present breezes. John Saunders, the proprietor/vineyard manager/winemaker at Poppaea Winery, mentioned that a few local enologists have identified “at least 11 different microclimates” within the 139-square-foot valley, so the range of wine grapes compatible to those potential “mini-AVAs” is broad – and speaks to the stunning diversity of the region.

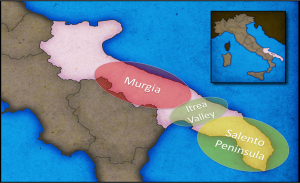

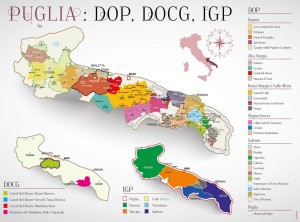

Red varieties flourish, especially those with their roots (no pun intended) in France, Italy and Spain. To that point, two wineries – Poppaea Winery and Principe de Tricase – are planted to white and red varieties spanning the length of Italy. Not surprisingly, Tempranillo craves the region’s sunshine and wide diurnal swings.

.

Other growers and winemakers opt for Rhone varietals, as Syrah, Grenache, Mourvedre and Viognier flourish in similar conditions in the Ramona Valley: rocky and barren soils, ample sunshine and a steady, moderating breeze, albeit without the destructiveness of the mistral. Woof ‘n Rose Winery was planted to Grenache Noir in 2004, with consultation from fifth-generation winemaker Marc Perrin of Château de Beaucastel—as well as Grenache rootstock from the French vineyard. Ramona Syrahs showcase a brooding, deep style much like their Cornas or St. Joseph cousins; those from Ramona Ranch Winery and Eagles Nest both offer elegant, haunting scents and flavors with earthiness and garrigue.

Wine fans searching for varieties above and beyond their tried-and-true classics will have a field day with offerings from the region. During our four days in the Ramona Valley, my husband and I visited 11 of the region’s 25 wineries, tasted 82 current releases – and had the good fortune to try six varieties we’d never before had the opportunity to taste: Alicante Bouschet, Refosco, Aleatico, Fiano, Sangrantino and Bolizao. Tannat, the pride of Madiran, is a featured variety at Ramona Ranch Winery, one of the wines my husband and I enjoyed thoroughly.

.

There’s no wonder why proprietors Marilyn and Steven Kahle at Woof ‘n Rose take pride in their Alicante Bouschet, the gorgeous teinturier: It’s generous, opulent, complex and undeniably enjoyable – and, my husband and I thought, a varietal that red fans would love if they tried it.

Speaking of Refosco: When was the last time we wine fans tasted one other than from their original northern Italian homes of Friuli or Trentino? Mike Kopp, proprietor/vineyard manager/winemaker at Kohill, offered us a barrel tasting of his signature Refosco, which nearly brought us to our knees.

Although heat-loving red varieties have a joyous home in the Ramona Valley, many whites do as well. Wine fans who enjoy their Chardonnays most when they’re flinty and zesty will appreciate the mineral influence of Mount Woodson and the nearby Cuyamacas; the elegant Chards featured at Lenora and Eagles Nest showcase that sculpted, sinewy quality as a counterpart to the variety’s richness.

Our Guest Blogger: Jan Crocker!

It’s impossible to overlook how well Mother Nature took care of us during our four days during the first week of August. During each of our visits to the 11 wineries, every proprietor, winemaker and vineyard manager gushed over the gorgeous weather that week—sunny, of course, but with soft breezes. It’s usually blazing hot, “about 100 degrees at this time of year,” our winery hosts pointed out. “But it’s only in the high eighties. Isn’t it beautiful?”

We couldn’t have agreed more. And the Ramona Valley AVA’s future looks equally gorgeous – with the distinct likelihood that California wine fans will soon discover its current excellence and stunning future.

Photo Credits: Jan Crocker

Are you interested in being a guest blogger or a guest SWEbinar presenter for SWE? Click here for more information!