Today we have a guest blog from Brenda Audino, CWE, who brings us up-to-date on the latest controversy at the TTB!

This is a follow-up to the blog “Oregon, Washington, and the AVA Shuffle: It’s Complicated”. As noted, the newly created appellation “The Rocks of Milton-Freewater” created some controversy. The controversy is not about the validity of the appellation itself – just about everyone agrees that “The Rocks” is a unique region. The controversy arises in who amongst the wineries will ultimately be able to use this new AVA on their wine labels.

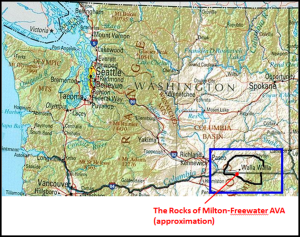

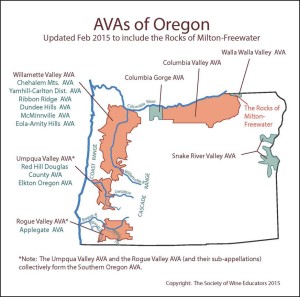

Here is a refresher regarding the Rocks of Milton-Freewater AVA: it is a sub-AVA nested within the larger multi-state Walla Walla Valley AVA, which is also nested within the much larger multi-state Columbia Valley AVA. The Rocks of Milton-Freewater AVA resides solely within the borders of Oregon, while the larger multi-state AVAs are predominately in Washington State while crossing over the border into Oregon. The controversy with this new AVA is that since it is entirely within the borders of Oregon, wineries must also be in Oregon in order to use the AVA on a wine label. Most wineries who call the Walla Walla AVA home are located in the state of Washington. This means that even if the winery owns vineyards or sources fruit in The Rocks of Milton-Freewater they will not able to utilize that The Rocks of Milton-Freewater AVA on their labels

The comments received by the TTB during the “open comment” period concerning this inability to use The Rocks of Milton-Freewater AVA were deemed valid by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) and worthy of consideration. This means that the TTB acknowledges that the current regulations would require wine that is fully finished in Washington and made primarily from grapes grown within The Rocks District of Milton-Freewater AVA to be labeled with the less specific “Walla Walla Valley” or “Columbia Valley” or “Oregon” appellations of origin.

On February 9, 2015 the TTB created a new proposed rule to address these specific concerns that were raised regarding this new AVA. This new proposed rule is titled “Use of American Viticulture Area Names as Appellations of Origin on Wine Labels”.

The TTB proposes to amend its regulations to permit the use of American Viticulture area names as appellation of origin on labels for wines that would otherwise quality for the use of the AVA name except the wines have been fully finished in the state adjacent to the state in which the viticultural area is located rather than the state in which the labeled viticultural area is located.

The TTB goes on to note that the purpose of an AVA is to provide consumers with additional information on wines they may purchase by allowing vintners to describe more accurately the origin of the grapes used in the wine.

The TTB does not believe this new ruling will cause consumer confusion since multi-state AVAs allow the wine to be finished in either state. They believe consumers are aware that appellation of origin is a statement of the origin of grapes used to make the wine and it would not be confusing or misleading if a single state AVA were finished in an adjacent state.

I don’t know if the TTB had any idea of the amount of comments this “fix” to the AVA system would generate, but this proposal opened up an entire flood of opposing views.

During the comment phase there were a total of 41 submissions. Out of these 41 comments there were 16 “For”, 18 “Opposed”, 6 “recommended a change to the proposal” and 1 “suggested an extension of the comment period”.

The “For” comments ranged from “providing consumers better knowledge of the origin of grapes”, “fair competition and accurately reflect origin of wines”, “increase business opportunities”, “where grapes are grown is more important than where wine is finished” and “grape shortages in adjacent states”.

The “Opposed” comments ranged from “confusion for consumers”, “support for local economy”, “the term ‘adjacent state’ is too broad, “undermines state labeling laws”, “large business will transport more grapes to take advantage of AVA names” and “creates deceptive labeling”.

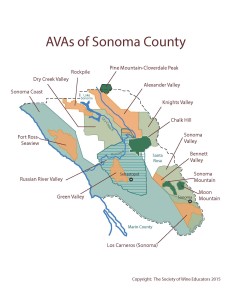

The comments that “recommended a change to the proposal” felt that the following wording on the proposal –“wines have been fully finished in the state adjacent to the state in which the viticultural area is located rather than the state in which the labeled viticultural area is located” – is too broad and encompassing. This, the commenter believes, has the potential to dilute current AVA status by transporting grapes across long distances. They recommended a change to the proposal to include “Wines finished in either state of a multi-state AVA can utilize any Sub-AVA that is nested within this multi-state AVA.” This would enable the wineries of Washington to utilize The Rocks of Milton-Freewater AVA, but not Willamette Valley AVA. This in effect would narrow the scope and alleviate many of the concerns raised by the commenters.

Unfortunately, I don’t have an end to this story. The comment period is now closed and the final ruling by TTB won’t be released until April 2016. For now though, if you want to find a wine from The Rocks of Milton-Freewater, you will need to search for an Oregon winery.

Post authored by Brenda Audino, CWE. After a long career as a wine buyer with Twin Liquors in Austin, Texas, Brenda has recently moved to Napa, California (lucky!) where she runs the Spirited Grape wine consultancy business. Brenda is a long-time member of SWE and has attended many conferences – be sure to say “hi” at this year’s conference in NOLA!

Are you interested in being a guest blogger or a guest SWEbinar presenter for SWE? Click here for more information