Today we have a guest post from renowned Wine and Spirits Educator Harriet Lembeck. Read on to hear Harriet’s take on Furmint!

If you haven’t already heard about Furmint – Furmint is the grape that makes the famed sweet wine Toakaji.

Aszu (‘dried up’ or ‘dried out’) grapes

When Samuel Tinon, a sweet-wine maker in Bordeaux, decided to move to the Tokaji region of Hungary, he was ready to make wine from its Aszu (‘dried up’ or ‘dried out’) Furmint grapes — grapes attacked by the desirable botrytis cinerea, or noble rot. These grapes are so concentrated that they have to soak in vats of young wine to dissolve their flavors. But when Tinon moved to Tokaji, botrytis was decreasing in his newly chosen region.

Expecting to make Aszu wines at least three times in a decade, the number of opportunities dropped to a little more than two times in a decade, and sometimes less than that. Due to climate change, a great deal of rain meant either no crop at all (as happened in 2010), or harvesting all of the Furmint grapes earlier — not waiting in the hopes of harvesting Aszu grapes — and therefore making dry white wines from earlier-picked grapes instead.

Asked about an apparent climate change, Tinon says: “We can’t see warming. What we see are erratic vintages with severe or extreme conditions — hot or cold, wet or dry. In the past, Tokaji Aszu was harvested at the end of October and the beginning of November, with botrytis and high sugars. This is still happening, but more often we have to change our production to dry Furmint wines without botrytis with an earlier September harvest, bigger crop, more security, more reliability and with a chance to get your money back.”

With winters becoming a bit warmer like in 2014, the fruit-fly population is able to ‘over-winter,’ and begin reproducing very early in the season, causing the spread of bad rot. This was told to me by Ronn Wiegand, MW, MS and Publisher of ‘Restaurant Wine,’ who is making wine with his father-in-law in Tokaji.

With winters becoming a bit warmer like in 2014, the fruit-fly population is able to ‘over-winter,’ and begin reproducing very early in the season, causing the spread of bad rot. This was told to me by Ronn Wiegand, MW, MS and Publisher of ‘Restaurant Wine,’ who is making wine with his father-in-law in Tokaji.

Ironically, Comte Alexandre de Lur Saluces, owner of Château de Fargues and former co-owner of the fabled Château d’Yquem, said that although his area is getting warmer and drier, he feels that “global warming could be a help for Sauternes, and enable any of those who chaptalize these wines to avoid the practice.” He continues, “Many people in Sauternes are producing dry white wines. Their production is increasing, and even Château d’Yquem is producing more dry wine.”

Hungarian winemakers from Tokaji are increasing dry white wine production as well. A new website, www.FurmintUSA.com, was created by 12 member wineries that presented a Furmint tasting in Sonoma, CA in November 2014. The Blue Danube Wine Company, which imports many wines from all over Hungary, has six producers from Tokaji that are producing dry Furmint wines (many from single vineyards). Martin Scott Wines imports Royal Tokaji’s dry Furmint wine, coming from the company co-founded by Hugh Johnson and Ben Howkins, in London. These wines are all delicious, showcasing the minerality of volcanic soil.

Considering that in 2014, Hungary abolished the categories of Tokaji Aszu 3 and 4 Puttonyos (baskets of Aszu grapes), leaving only the sweeter 5 and 6 Puttonyos examples, the door has been opened for Dry Szamorodni. This rich, dry white (amber colored) wine produced from Furmint grapes has a portion of grapes which have some botrytis co-fermented to dryness, and also uses some flor yeast, giving the wine some fino or amontillado Sherry-like flavors.

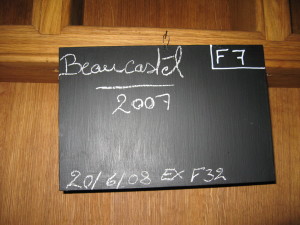

This wine is very laborious and time consuming to produce. The 2007 Tinon Dry Szamorodni is the current vintage in the market, released after a minimum of 5 years of aging. This is a unique wine, a keeper, and is important to the history of Tokaji, linking the modern dry wines to the traditional Aszu wines.

If you haven’t tried it – you should!

HARRIET LEMBECK, CWE, CSS, is a prominent wine and spirits educator. She is president of the renowned Wine & Spirits Program, and revised and updated the textbook Grossman’s Guide to Wines, Beers and Spirits. She was the Director of the Wine Department for The New School University for 18 years. She may be contacted at hlembeck@mindspring.com.

HARRIET LEMBECK, CWE, CSS, is a prominent wine and spirits educator. She is president of the renowned Wine & Spirits Program, and revised and updated the textbook Grossman’s Guide to Wines, Beers and Spirits. She was the Director of the Wine Department for The New School University for 18 years. She may be contacted at hlembeck@mindspring.com.

This article was originally published in the article was originally published in

Beverage Dynamics Magazine – reprinted with permission!