An updated list of wine appellations—DOPs and IGPs—published by Spain’s Ministry of Agriculture (Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación) reveals that the Spanish wine region of Granada has been promoted to a Denominación de Origen (DO).

For the number-crunchers among us, this means that (as of June 2021) Spain now has 68 DOs, 2 DOCa’s, 7 VCIGs and 20 Vinos de Pago…for a total of 97 DOPs. See the attached List of DOP and VT Wines from Spain June 2021 for the names and numbers via straight from the source documentation.

Granada was was previously listed as a Vino de Calidad con Indicación Geográfica (VCIG)—which placed it in the top-tier of Spanish Wine Regions, but (theoretically) a step “lower” than the DOs.

According to the Pliego de Condiciones for the Granada DO, the appellation is approved for the production of a range of wine types and styles, including red, white, rosado (rosé), sparkling, and late harvest (de uvas sobremaduradas/over-ripe grapes). Here is a list of allowed grape varieties for the three main styles of wine:

Red (Tinto) and Rosé (Rosado): Tempranillo, Garnacha Tinta, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Syrah, Pinot Noir, Monastrell, Romé, and Petit Verdot.

Red (Tinto) and Rosé (Rosado): Tempranillo, Garnacha Tinta, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Syrah, Pinot Noir, Monastrell, Romé, and Petit Verdot.

White (Blanco): Vijiriego (Vijariego), Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Moscatel de Alejandría (Muscat of Alexandria), Moscatel de Grano Menudo (Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains), Pedro Ximenez, Palomino, Baladí Verdejo (Cayetana Blanca), and Torrontés.

Sparkling (Espumante): Vijiriego (Vijariego), Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Moscatel de Alejandría (Muscat of Alexandria), Moscatel de Grano Menudo (Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains), and Torrontés.

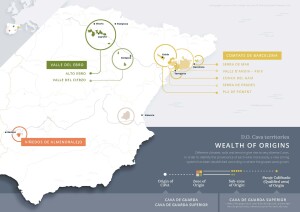

The Granada DO covers the entirety of the Province of Granada. Granada is located on the Mediterranean Coast and stretches across the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range to the border with Murcia and Castilla-La Mancha. The area is transversed by several rivers, the main one being the Genil (a tributary of the Guadalquivir). The central/northern portion of the province covers the Altiplano de Granada (Granada High Plains).

A single sub-region—Contraviesa-Alpujarra, located along the Mediterranean Coastline—has been approved. Sparkling wines produced using a minimum of 70% Vijiriego (Vijariego) supplemented by Chardonnay and Pinot Noir are a specialty of the Granada-Contraviesa-Alpujarra DO.

References/for more information:

- List of DOP and VT Wines from Spain June 2021

- Pliego de Condiciones-DO Granada

- http://www.dopvinosdegranada.es/en/promocion_y_eventos.php

- Map of Spanish PDO Wines – November 2020

Post authored by Jane A. Nickles…your blog administrator: jnickles@societyofwineeducators.org