.

Today we have a guest post—the third and final in a series—by an author we have all gotten to know by the nom de plume of Candi, CSW. Click here to read the first article in the series, as Candi takes us on a tour of the Grand Canyon, and click here for the second stage as she makes her way through New Mexico. Today, Candi takes us on the final leg of her southwest sojourn with a trip through Arizona—with plenty of local wine along the way!

It was time to leave Santa Fe with good memories and ideas for our next trip there. Such a great destination that we were glad we allowed four nights for exploration. On to the final stop: Scottsdale, Arizona.

We had our longest drive of the trip from Santa Fe to Scottsdale. But it was mostly interstate highways with minimal traffic. We took our time, allowed frequent rest and stretch breaks, and enjoyed the view as scenery transitioned from canyons and mesas to deeper red rocks and pure desert. I couldn’t help but wonder if Saguaro cactus is used for margaritas, like the Prickly Pear of the Yellowstone area.

We had traveled to and through the Phoenix area many times for business and family visits. And, while we have enjoyed the Sedona area as a vacation stop, it seemed that Scottsdale had more of a resemblance to Santa Fe. The area offered an opportunity for more museum exploration and shopping. And, once I found that Scottsdale now has a wine trail, the decision was made.

.

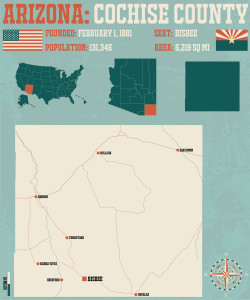

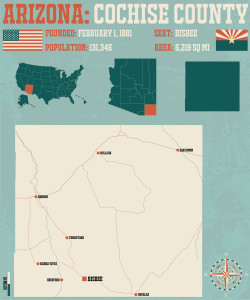

Many Arizona wineries are located in remote areas of the state, such as Cochise County. Cochise appears to be one of the southernmost counties, with the Mexican border to the south. (For more details and another perspective, see a 2016 SWE blog post titled “Arizona Wines are gaining recognition — Imbibe and take notice!“) Some wineries have tasting rooms in Cochise County. I can see, however, that it would make sense to take some tasting rooms to the populous areas. Scottsdale appears to have the demographics to be a great location for an urban area tasting room.

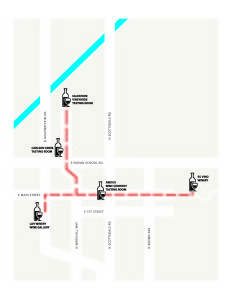

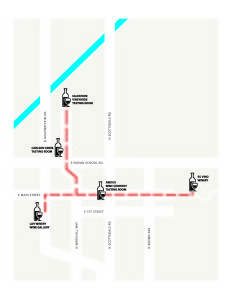

Multiple wineries had already come to the same conclusion as I did about Scottsdale. The Scottsdale Wine Trail now features five winery tasting rooms/wine bars. I suppose an ambitious sort would be able to walk to all of them for tasting in a single day. That’s not our style, and the trip planner (me) had to account for temperatures of 90+ degrees, arid weather, and sun. Another opportunity for wise pacing. We chose to allow the morning for a museum, and the afternoon for two wine tastings.

We had checked into our hotel on a Friday evening. Quiet in-room dinner, a very good night’s sleep, then great morning coffee. A full Saturday on the agenda. The weather gods had smiled upon us; temperatures in the 80s to about 90. Cooler than expected equated to walk-friendly and wine-friendly.

We found that, unlike Santa Fe, free, underground, shaded parking is readily available in Scottsdale. Secured our shaded, delightfully cool space. Short walk to the Museum of the West, an affiliate of the Smithsonian. This museum was not widely mentioned in mainstream travel guides, so it may qualify as another “hidden gem”. And a valuable gem it is.

Given that we visited the Museum on a Saturday, I was concerned about crowding. Not at all. Very quiet, plenty of helpful docents. Exhibits of, it seemed, anything and everything Western culture-related. Paintings, pottery, ceramics, wildlife. All of these were well-done and enjoyable.

.

But two exhibitions were just outstanding. One featured Western clothing, leather goods, and accessories such as spurs and saddles. All of these were items that either were or could be actually used by ranchers, cowboys, law enforcement, etc. And the beautiful leather tooling! Some of the saddles struck me as works of art.

The second standout featured a vast collection of movie posters and film history. OK. This sounds lightweight and even a bit immature, but the depth and breadth of the display had me taking notes. We have since viewed a western movie or two that have demonstrated great acting, scenery, and a touch of history. Before we knew it, we had spent more than 3 hours exploring the Museum.

Meanwhile, the wine tasting rooms had begun the afternoon hours. We left the Museum of the West a bit reluctantly, wearing our stickers so we could get back in if time allowed. But two tasting rooms were calling, and one must have priorities.

.

Old Town Scottsdale, a brief walk from the Museum, features shopping, dining, and the Wine Trail. We did a quick reconnaissance of the shops; nothing compelling for us. On to the all-important afternoon stops.

Airidus Wine Company combines a tasting room and wine bar. The wine is produced in Willcox (Cochise County). Five wines of your choice per tasting; a one-bottle purchase of the higher-end bottlings waives the tasting fee. Fair enough. My tasting included Malvasia Blanca, Rose’ of Mourvèdre and Grenache, Grenache, Malbec and Petite Sirah. Service was excellent, with plenty of information volunteered in response to my geeky questions. My only criticism: while my palate is still developing, I clearly recognized that the Petite Sirah was corked. All of the other wines were purchase-worthy.

But it seemed to me that the reds were the most attractive. Overall impressions: deep, compelling, long finish, oak, varietally-correct fruits. So this frugal soul was drawn to not one, but two bottles. Malbec and Grenache. Plus 2 bottles of their version of casual wines, the Tank Blends. One white (Viognier, Sauvignon Blanc, Chenin Blanc, Chardonnay and Malvasia Blanca). One red (Malbec, Mourvèdre, Syrah and Montepulciano). Blends, indeed!

Map of the Scottsdale Wine Trail via: http://www.scottsdalewinetrail.com/

Carlson Creek is another tasting room with wine bar. This venue was very busy, but Wendy, the sole server, was efficient, friendly, informative, and kept moving. She gets credit for noting and understanding my CSW pin. She returned to us frequently so we could learn from each other. What fun!

With a choice of 12 wines, narrowing the field was a challenge. We sampled Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, a Rose’ of Grenache, Sangiovese, Mourvèdre, a GSM blend and Syrah. Okay, maybe I didn’t narrow the field too well; but, I had my trusty designated driver. I was walking a short distance back to the car. I kept hydrated. It was my last wine stop of the trip. I was relaxed and enjoying myself. Did I mention I was on vacation?

Decisions, decisions. The whites were enjoyable, and I can see how a white-only afficianado would have several options. But we enjoy whites, Rose’ (technically a red, but always a bridge wine to me), and reds. The reds of Carlson Creek were even more appealing to me than those of Airidus. Complexity, balance, evolving-over-minutes. Food pairings already in the mind. Evoking memories of a warm to hot climate.

Two bottles waived the tasting. Not. A. Problem. After deliberation, wine one was Mourvèdre, because of the attractive leather aromas and flavors. Could this have been a flashback to the exhibition at the Museum of the West? Possible.

Wine two, Rule of Three as a well-done GSM and for potential food-friendliness. Wine three, our favorite, the Syrah. The deep, intense, varietally-correct Syrah. Yes. If you are a Sryah lover and visit, please, please try this wine.

More water, another short walk, wine returned safely to car in cool space. Yet more water and another short walk to pick up the takeout we’d ordered. The dining establishments were not yet busy and we wanted to exit before the Saturday night crowd began. Dinner secured, all missions accomplished.

.

Our final evening of the vacation. Plenty of time to begin packing and organizing for the final day of driving. Hydration, hydration, hydration. And, when we were ready, a great meal courtesy of Cowboy Ciao. This place had come highly recommended; they were correct. One of the best chopped salads I’ve ever had, truffle macaroni and cheese, and a wine pairing of Vivac Sangiovese.

Another good night’s sleep. On the drive home, I began to reflect on the many things that went well on our trip. Key success factors, to use business-speak. Pacing ourselves. Blending culture, shopping, moderate walking, wine tasting. Recognizing when it was wise to end the day and elevate feet. Stretch breaks on the road. Agenda to minimize crowds and noise. These may not be critical items for go-go-go extroverts. But they are for, ahem, aging introverts.

What about the common themes of Southwest wine? Based on my initial impressions, of course. Further study is clearly indicated. How’s that for justification of already considering what to do on the next trip?

.

Shared characteristics we experienced were young wineries, many varietals per winery, more reds than whites. Maybe these vintners are still trying to establish a strategy of which grapes grow best, and then plan to focus on those. Maybe not. We also noted more reds than whites, which may equate to warm, arid climate. Pleasant, approachable whites. Clearly more compelling reds. If I had to find comparable areas, the Sierra Foothills for the New World and Spain for Old World would suffice.

Now, we have the post-trip enjoyment of seeing whether our decisions in the short-term reward us as the drinking windows begin to open. For some reason, I am optimistic.

Southwest Salute’, Cheers, and Happy New Year!