Today we have a guest post from Justin Gilman, CSW, who tells us about the blossoming wine industry in his adopted state.

Colorado’s wine industry began back in 1890 when then-Governor George Crawford planted roughly 60 acres of vines in the Grand Valley near Palisade. Just over a decade later, there were over a thousand Colorado farms involved in grape growing.

These days, the majority of Colorado’s wine production is focused in the West-Central part of the state, near the town of Grand Junction. Colorado currently boasts two AVAs: Grand Valley and West Elks. About 75% of the state’s one hundred-plus wineries are located in the Grand Valley AVA while the remaining 25% are in the West Elks AVA. Other growing regions include McElmo Canyon, Montezuma County, South Grand Mesa, Freemont County, Olathe County, and Montrose County.

Colorado’s continental climate coupled with its famous high elevation means that grapes grown here receive a tremendous amount of sunlight with minimal cloud cover. However, the grapes also benefit from an excellent diurnal temperature variation – meaning the sunshine and heat help to unlock sugars during the day; and the exceptionally low temperatures help to retain acidity at night.

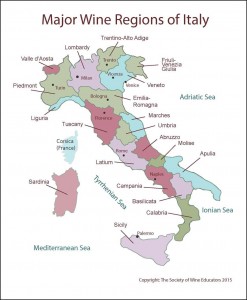

Colorado’s elevation, foliage and mountain ranges have been compared to that of Northern Italy’s Alto-Adige region. With the highest wine growing elevation in North America, (Grand Valley 4,000-4,500 ft. and West Elks up to 7,000 ft.) these chalky and loam soils see as many degree-in days as Napa, Tuscany and Bordeaux in a shorter period of time.

The grape varieties grown here are on par with other wineries across the country. Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Chardonnay and Moscato are staples, with some experimentation of blends between wineries. Rhône varieties do particularly well in Grand Valley, and Tempranillo is showing great promise in the West Elks AVA.

As in any wine country, Colorado wineries offer a wide range of products. Taking advantage of the sunny skies and over 300 days of yearly sunshine, some Colorado wineries create consumer-friendly wines leaning on slightly higher sugar levels. Softer Cabernets, Chardonnay/Moscato blends and plenty of sweet fruit wine options like that of Carlson Vineyards Cherry & Peach wine to St. Kathryn’s “Apple Blossom” and “Golden Pear” are popular wines, known for being friendly to a beginner’s palate.

Some of the best wines in the state are produced by Ruby Trust Cellars of the Castle Pines area. Ruby Trust Cellars, led by owner Ray Bruening and winemaker Braden Dodds have produce wines with rough-and-ready names such as “Gunslinger”, “Fortune Seeker” and their recent addition “Horse Thief”. Located roughly 20 miles South of Denver, Ruby Trust puts out a handful of limited production blends and single varietal wines that have caught the eye of some well-known critics. Sourcing fruit from growers in Grand Junction, Ray and Braden uphold the highest integrity when creating their wines. Retailing just over $30 a bottle, their wines are individually numbered with labels reminiscent of the historical mining era of Colorado. Ruby Trust is considered amongst Colorado’s best, found in selected Aspen and Vail restaurants and resorts, as well as specialty wine shops throughout the Denver area.

Colorado has also embraced the idea of the “urban winery,” including Bonaquisti Wines, located in Denver’s Sunnyside neighborhood. Bonaquisti Wines proudly declare themselves to be procurers of “Wine for the People!” With wine in kegs, refillable growlers, and live music every Friday night, it seems like they are living up to their motto quite well.

One of the most intriguing wineries in Colorado is undoubtedly the Infinite Monkey Theorem. (The name is derived from the theory that a monkey striking typewriter keys for an infinite amount of time will, eventually, create the works of Shakespeare.) Founded by Ben Parsons, the winery was originally housed in a graffiti-covered Quonset hut. While the business is now housed in a 20,000-square foot warehouse, they still tend to do things (shall we say) a bit differently, and feature such items as wine in cans and a “bottles and bacon” gift pack.

Yearly, Colorado’s best wines are judged at the Governor’s Cup in Denver, and an alternate event with growing popularity, the Denver International Wine Competition. The Governor’s Cup focuses on Colorado Wines, presented by the Colorado Wine Board, to discover the “Best of the Best” in Colorado, while the Denver International Wine Competition welcomes any wine with the potential of being distributed in Colorado. Previous winners of the 2014 Governor’s Cup include Canyon Wind Cellars 2012 Petit Verdot, Grand Valley AVA, $30 and Boulder Creek Winery, Boulder, 2013 Riesling, Colorado, $16. The 2015 top scorers include Bonacquisti Wine Company – 2013 Malbec, (American) and Bookcliff Vineyards 2014 Viognier, Grand Valley AVA.

The Colorado wine industry is consumer friendly and each year is continuing to grow by leaps and bounds, striving to be traditionally focused. For the future, the industry is focused on minimizing blends, gradually creating more structure- driven wines, and slowly educating the consumer palate – a noteworthy goal in a state known for its beer consumption. Given the terroir, and talent, and these noted goals, the future looks bright for the Colorado wine industry.

Justin Gilman, CSW is the Store Manager/Buyer for Jordan Wine & Spirits, a leading retailer in Parker, Colorado, located in Denver’s South Metro area. With over 15 years in alcohol beverage retail, in the major markets of Orange Co., and Los Angeles California, he now resides in Denver Colorado, where his skill set as an operator and buyer are utilized for both retail and as a consultant in the industry.

Are you interested in being a guest blogger or a guest SWEbinar presenter for SWE? Click here for more information